West African Coelacanths?

© Loren Coleman 2020

International Cryptozoology Museum, Portland, Maine

Searching for a new species of coelacanth (in the genus Latimeria), especially in the Atlantic Ocean, may involve conducting detective work, ethnographically, in West African art.

The Coelacanth Rediscovered

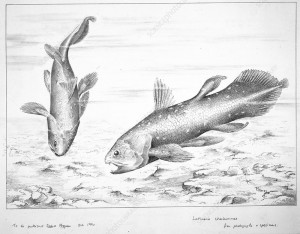

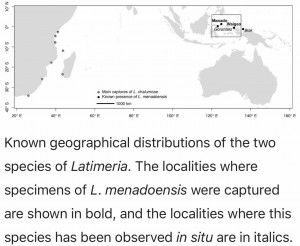

The West Indian Ocean coelacanth, thought to have become extinct in the Late Cretaceous, about 66 million years ago, was rediscovered in 1938, off the coast of South Africa. The Comoro Islands specimen (second overall) was discovered in December 1952. Then sixty years after the 1938 find, in 1998, a second extant species was rediscovered off North Sulawesi, Indonesia.

The credit for these coelacanth rediscoveries goes to Captain Hendrick Goosen, Marjorie Courtney-Latimer, and J. L. B. Smith for the West Indian Ocean coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae) and to Mark V. Erdmann and Arnaz Mehta for the Indonesian coelacanth (Latimeria menadoensis).

There remains continued speculation that more species of coelacanths remain to be discovered.

Philip J. C. Dark’s Legacy

Did the late anthropologist Philip J. C. Dark unknowingly discover hints to the existence of West African coelacanths in West African art?

Philip J. C. Dark, Ph. D., was British, an art historian, anthropologist, painter, and photographer. Born on May 15, 1918, in London, the eventual Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at Southern Illinois University-Carbondale (SIU-C) died on April 4, 2008, in St. Mawes, Cornwall, England. He was a leading authority on indigenous arts, particularly of Benin and the Pacific.

Dark joined the Department of Anthropology at SIU-C in 1960, was chair of the Department in 1963-1967, and retired in 1978. When I was on campus and studying in the Anthropology Department in 1965-1969, I took coursework in what was referred to in Midcentury America as “primitive art” from Professor Dark. He was a friendly and approachable member of the faculty.

After Dark retired from SIU, he returned to England, where he continued to be very active. In 1975, Dark had begun editing the Pacific Arts Association Newsletter (which became the journal Pacific Arts in 1990) and served as the editor for 25 years. His foundation work in Benin mastery was well-established.

Philip Dark had worked extensively with Benin art, and understood what its motifs represented. His obituary writer, fellow SIU anthropologist Jerome Handler noted:

Dark finished writing his dissertation on a ship bound for Nigeria, where he spent more than two years at the West African Institute for Social and Economic Research at University (College) Ibadan. He first held an administrative position then became a senior research fellow for the institute’s Benin History Scheme, which he had helped organize. He was specifically charged with documenting all known Benin bronzes and working out a historical chronological framework for the art of this legendary West African kingdom, noted for the high quality of its traditional brass-casting and ivory-carving. He continued his studies of Benin for many years after leaving West Africa (by 1966 he had data on close to 7,000 objects from more than 200 collections and about 10,700 photos), and over the years he produced numerous scholarly articles, museum catalogs, and specialized monographs on Benin art and technology (e.g., 1962, 1973, 1975, 1982; Dark and Hill 1971; Forman et al. 1960). [Handler, 2008.]

Dark’s “Unknown Species” Notes

In 1960, Artia designed and produced for Batchwork Press Limited of London a significant book simply entitled Benin Art. The “Photographs” were by W. and B. Forman, and the “Introduction” and “Notes to the Plates” were by Philip Dark.

As Dark writes in his “Introduction,”

Benin art is essentially a court art; it is not an art of the people. Its principal functions are commemorative, ritual and ceremonial. The bronze plaques are historical documents, recording people and events….(Forman and Dark, 1960, p. 11).

Benin Art (Forman and Dark, 1960) contains 92 plates of the Formans’ photographs and Dark’s corresponding notes describing the objects in the photographs.

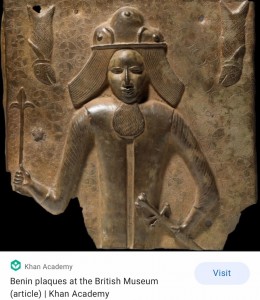

The specific date these Benin bronzes were first seen in the West is exactly known. “The year 1897 marks the discovery of Benin art by Western Europe,” writes Philip Dark (p. 9) in his “Introduction.”

Colonial forces, the so-called “Punitive Expedition” of British was mounted against the Benin Kingdom, and captured Benin City (in what is today Nigeria) on February 17, 1897. Dark observed, “The members of the Punitive Expedition were amazed to find in Benin City an enormous quantity of bronze castings, ivory carvings and other art objects.”

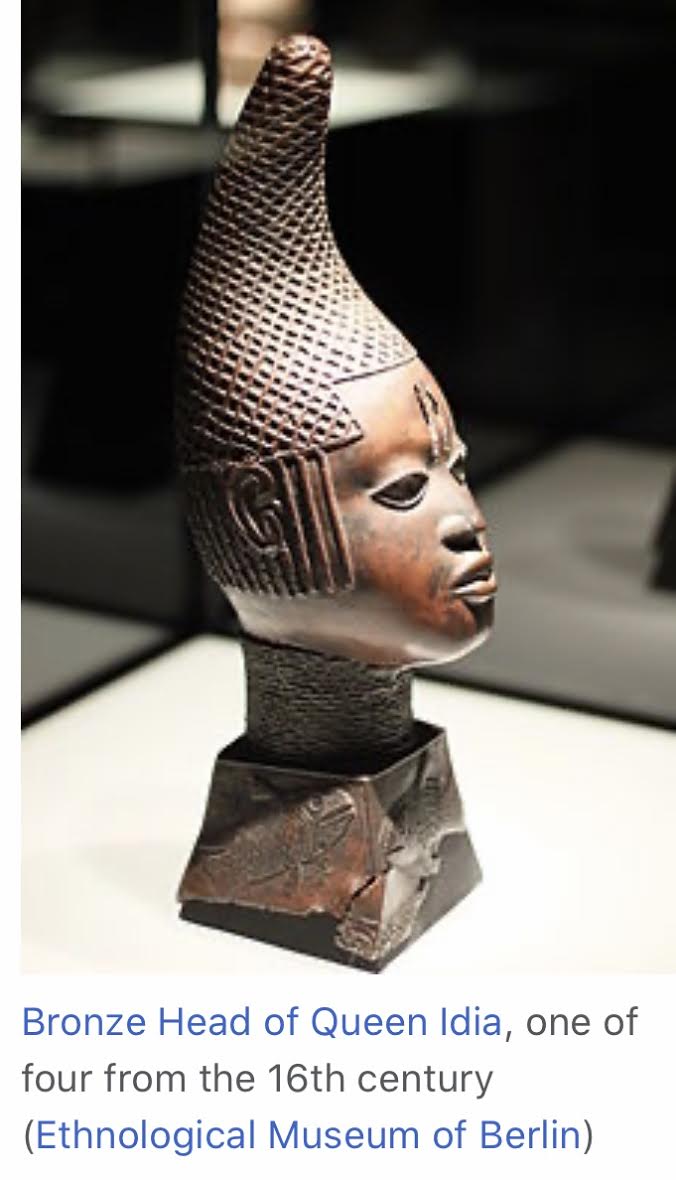

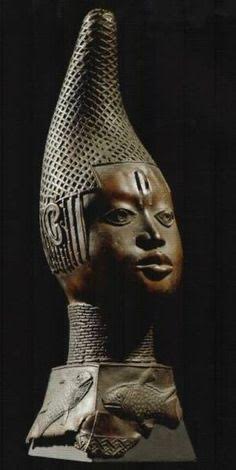

Besides wooden and ivory carvings, extremely high quality objects of what have come to be known as the Benin Bronzes was looted by the British and taken from the royal locations. The actual number appears to have been about 1000 pieces, and most of those ended up in English and German museums, mostly the British Museum and Ethnological Museum of Berlin collections.

As Dark demonstrated in Benin Art, pre-20th and early 20th century photographs from older books dates the Benin bronzes to before the re-discovery of the coelacanth.

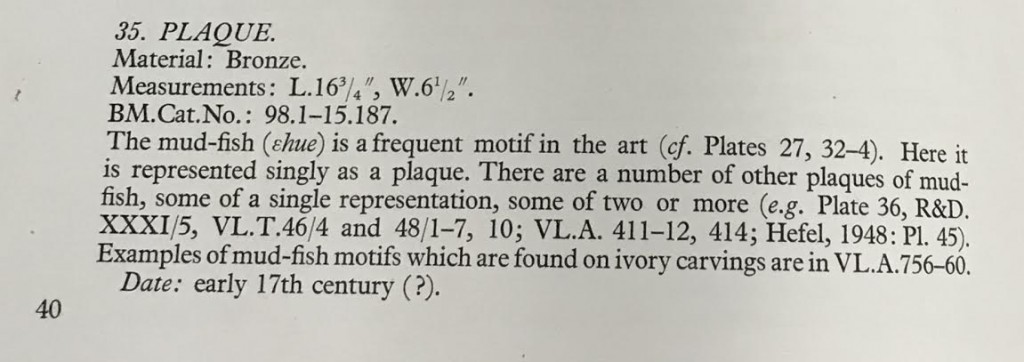

Dark writes in his notes for Plate 35, “The mud-fish (shue) is a frequent motif in the [Benin] art.”

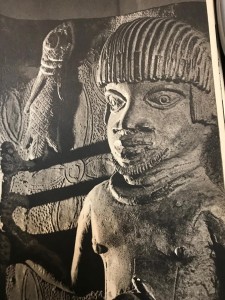

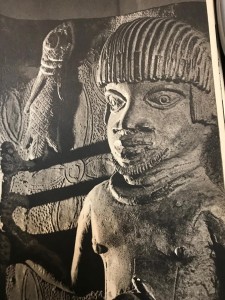

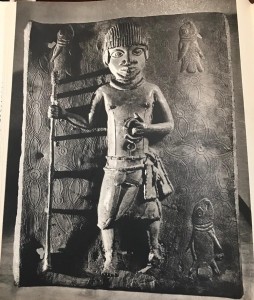

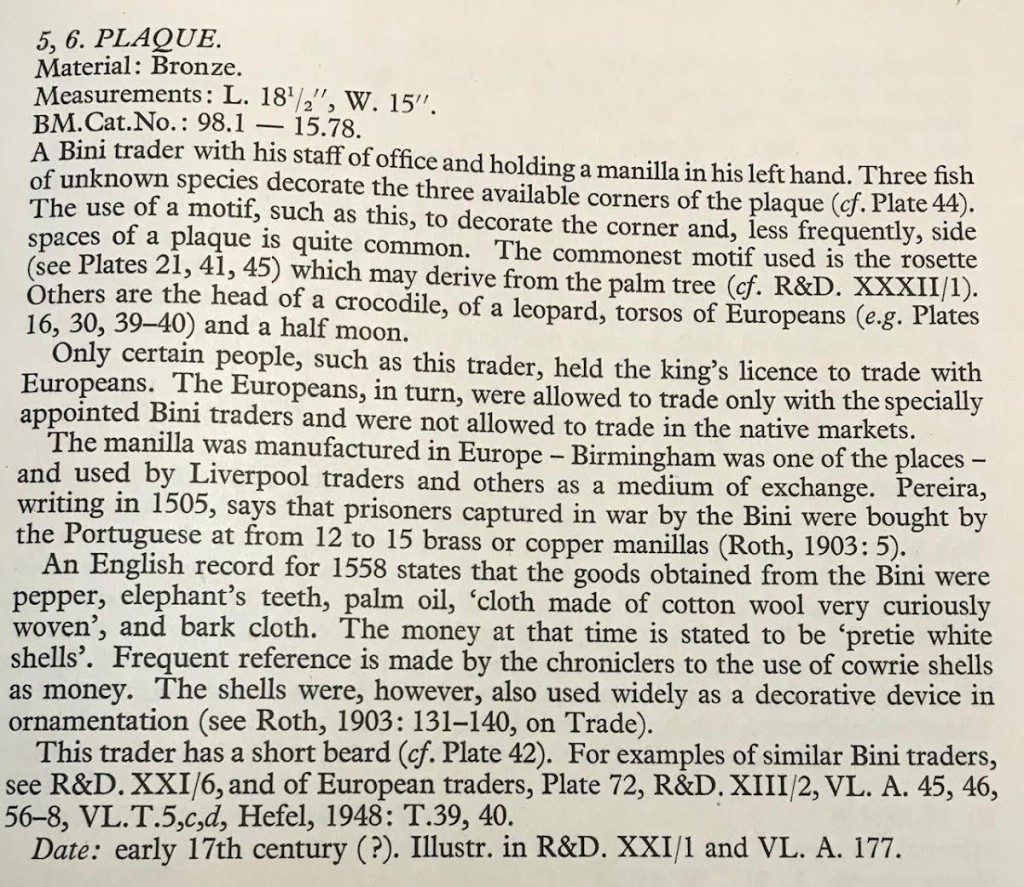

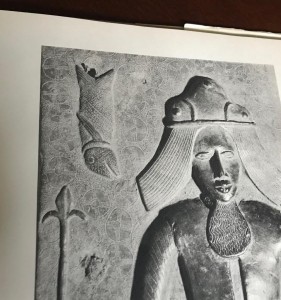

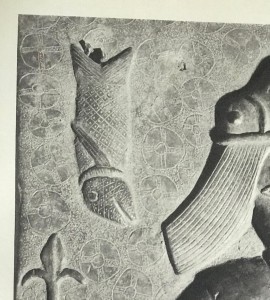

So it is with some surprise that for Plates 5 and 6, we find Philip Dark writing that these have the identity of “three fish of an unknown species.”

The abbreviations R&D refer to Read and Dalton, 1899, and VL to Luschan, 1919. Dark also mentions this plaques dates from the early 17th century (?), thus establishing a firm pre-1938 provenance.

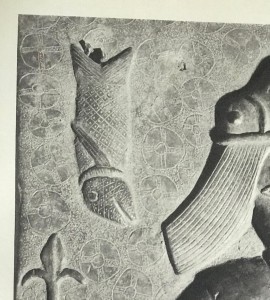

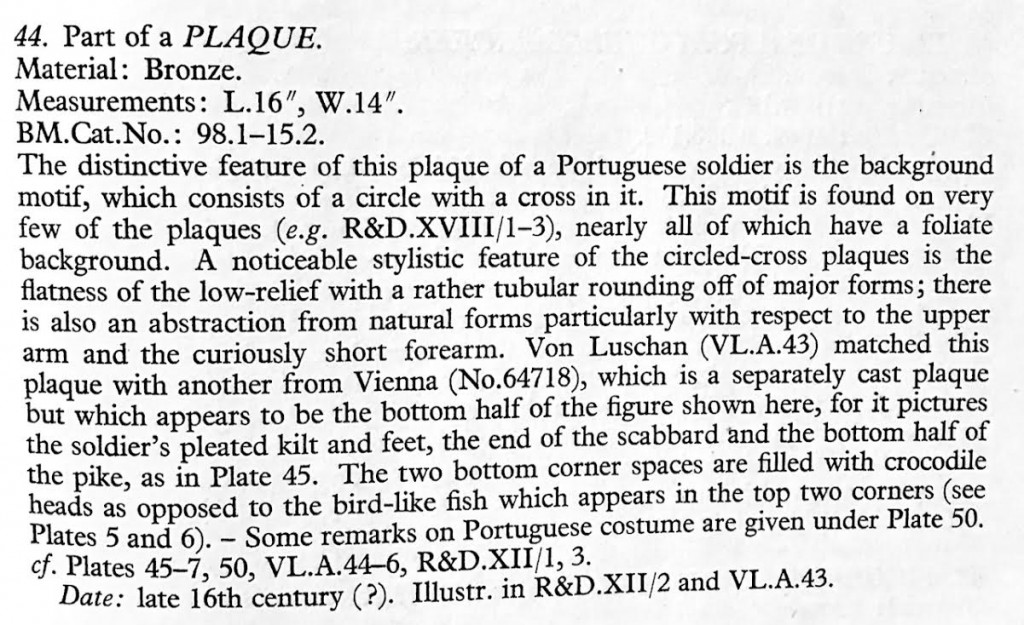

Furthermore, the “unknown species” of fish in Plates 5 and 6 is compared to the fish in Plate 44. Dark terms it a “bird-like fish” on this plaque.

The plaque shown in Plate 44 has been featured more fully in recent years.

The Queen Mother’s Fish

In addition to the fish that Dark pointed out, a very coelacanth-like fish was fashioned on Queen Idia’s pedestal. She was the mother of Esigie, the Oba of Benin who ruled from 1504 to 1550.

Catfish or Coelacanth?

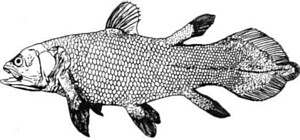

The mystery unknown species does not appear to match the most frequent fish found in Benin bronzes: the sharp tooth catfish. Could they be coelacanths?

In response to my inquiry asking for an opinion on September 9, 2020, of French cryptozoologist Michel Raynal, he replied on September 10, 2020,

It does not look like a coelacanth to me : the tail does not show the 3rd (epicaudal) lobe, unless you consider the two fins below and above the round tail being a part of the tail itself — but if so, some dorsal and ventral fins would be missing in a coelacanth fish.

Fair enough. There is every likelihood they are not coelacanth, known to most readers via elegant sketches of dead specimens recovered. But let us look at some items of note.

Benin Mudfish

Philip J. C. Dark appeared to be certain these fish of “unknown species” were not what were popularly called “mudfish” in English and shue in Benin.

There are two types of mudfish: One can give a powerful electric shock that is often referred back to the Oba’s immense power over his enemies. Another one is known for their ability to survive on land as well as in the water and this ability is perfect for illustrating the Oba as a divine king who can be part of the human and spiritual realms. The mudfish is an important symbol in both Yoruba and Benin cultures. ~ Asiri Magazine

In the note to Plate 35, Dark writes:

Photographs of Benin bronzes’ mudfish illustrate how different they look from the Benin “unknown species.” Most Benin mudfish are identified as African sharp tooth catfish (Clarias garlepinus), a species of catfish of the family Claridae, the air breathing catfishes.

The mudfish represented in Benin bronzes demonstrate the flexibility of the body of the living African catfish.

This is Plate 35 and 36 from Benin Art (Forman and Dark, 1960) showing “the mud-fish” and “four mud-fish.” They look different than the “unknown species” that were unidentified by Dark.

Representing Coelacanths

In a perfect world, all coelacanths would look like textbook specimens. But in Benin in the past or anywhere today, this is not a perfect world.

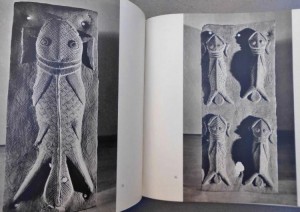

Kigombe 2 with fishers, Tuwe Saidi and Jumbe Kombo. Note damage to fins. Damage was more extensive when examined, after storage, in June 2005. Photograph: E. Verheij. (Fig. 4).

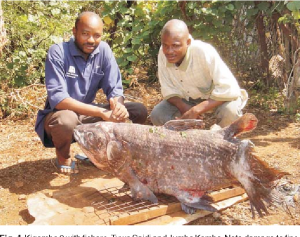

How was the first coelacanth first drawn? Marjorie Courtney-Latimer’s initial sketch to J. L. B. Smith mirrors how a hastily made ethnoknown drawing might appear.

Even some modern artists completely delete the epicaudal lobe.

Also, as Hans Fricke (1987) has demonstrated, the coelacanth can change the shape of its posterior fin, when swimming.

Head Stands of the Coelacanths

While the known species of coelacanth are frequently illustrated as swimming horizontally, they are known for their usual mode of swimming too.

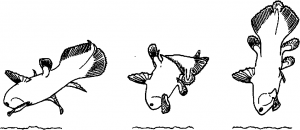

“Fin movements during head-stand (read from left to right). Notice stroking of caudal and epicaudal fin until the body stands in a vertical position. Time between frames l-2 = 9 s, 2-3 = 8 s.” ~ “Locomotion, fin coordination and body form of the living coelacanth Latimeria chalumnae,” by H. Fricke and K. Hissman, Environmental Biology of Fishes, 2004, Fig. 19.

“When hunting they orient themselves vertically, allowing an electrosensitive rostral organ in their snout to assist in the detection of prey.” ~ “Coelacanths,” by Mark Robinson, Benaroya Research Institute at Virginia Mason, and Chris T. Amemiya, Department of Biology University of Washington, Current Biology, Vol 24, No. 2, R62, 2014.

“During its nightly foraging swims, Latimeria was often seen to perform head-stands, in which it rotates its body into a vertical position, with its head near the bottom and its caudal fin curved perpendicular to its body. It then held this position for two or three minutes at a time. This curious behavior may be used when it is scanning the bottom with its putative electoreceptive rostral organ, or it may be a reaction to the bright lights of Prof. Fricke’s submersible.” ~ Latimeria chalumnae Smith, 1939. Coelacanth. Fishbase.de

Latimeria chalumnae Smith, 1939. Coelacanth. Pencil drawing by Peter Forey showing a coelacanth standing on its head and holding its snout just above the seabed, detecting small electric fields produced by its prey. Natural History Museum, London, UK.

Intriguingly, the orientation of the Benin “unknown species” of fish are not horizontal, but in vertical positioning. Could this relate to its unusual swimming posture?

Coelacanths’ Ranges and Rumors

The future discoveries of populations of coelacanths are going to occur. There is no doubt that explorations ~ via on-site searching, indigenous people interviewing, and investigations of old ethnographic records ~ will reveal results.

Michel Raynal of France has written in some depth on the possible wide distribution of coelacanth around the globe. Known from the east coast of Africa and thus the western side of the Indian Ocean, and from the western side of Indonesia and thus the eastern side of the Indian Ocean, the known coelacanth range makes some sense. While it may be a stretch to think of some West Africa encounters between coelacanths and Benin artisans, it is not impossible. Certainly, it may be a worthy exercise to explore more ethnographic investigations.

As Raynal and Mangiacorpa (1995) reference in their comprehensive survey, ”Out-of-place coelacanth,” the German zoologist Burchard Brentjes (1972) attempted to “demonstrate an early discovery of the coelacanth by Indian Moghuls, from an artistic representation of the early 18th century, on an Indian miniature from Lucknow.”

Raynal found Brentjes’ demonstration “not very convincing.” Nevertheless, examinations of ethnographic materials should continue to give future worthwhile results.

Cryptozoologically critical thinking Cameron McCormick gives an overview of the article by Raynal and Mangiacopra (1995), which discusses “the history of the coelacanth from not-so-out-of-place specimens from South Africa, Madagascar, and Kenya and then goes on to speculate on more exotic habitats. There were very vague reports of the fish from Bermuda and Korea mentioned in a letter to Prof. Smith (the describer of the fish) which were in all likelihood cranky. Interestingly he mentioned earlier reports of the Indonesian coelacanth (from 1995) that could have made this a genuine ex-cryptid had anybody actually payed attention to the reports and looked for the fish. Australian, Spanish, Jamaican, Californian, and Floridian coelacanths have all be claimed as well but the cases are vague enough that they may be anglerfish or (quite improbably) stray lungfish. Unidentified scales were also mentioned from those locations but the most famous artifacts are the silver coelacanths.”

There frequently is good news from those in search of coelacanths:

Prior to September 2003, coelacanths had not been officially recorded from waters off Tanzania. A sudden spate of coelacanth catches has resulted in 21 confirmed and several unconfirmed specimens being recorded. Nineteen specimens were caught in six months off Tanga, including six in one night. Nowhere else in the world have so many coelacanths been caught in such a short time. The reason for this sudden increase in catches is uncertain. There is concern that the impact of this fishing mortality might be threatening the population. Morphological and meristic data from Tanga specimens indicate that they are not notably different from those examined elsewhere in the western Indian Ocean. Tanzanian authorities plan to determine the size and conservation status of coelacanth populations so that informed conservation decisions might be made.” ~ “Coelacanth (Latimeria chalumnae Smith, 1939) discoveries and conservation in Tanzania. ~ by B. Benno, E. Verheij, J. Stapley, Chikambi Rumisha, B. Ngatunga, A. Abdallah, H. Kalombo; South African Journal of Science, 2006.

Loren Coleman, International Cryptozoology Museum, and Jerome Hamlin, dinofish, with a Japanese coelacanth model, 2013.

At the 2016 International Cryptozoology Conference in St. Augustine, Florida, Dinofish’s Jerome Hamlin shared with the attendees his pursuit of evidence for coelacanths being caught in the Solomon Islands of the South Pacific. In 2019, he extended his interviewing in Hawaii. (See #50, #58, #60, and #69 at Dinofish.)

This past January 2020, Kadarusman, et al. (2020) published DNA findings noting the Indonesian coelacanth has two lineages.

Figure from Kadarusman, et al. (2020)

Reflections of Caution

Michel Raynal had predicted the coelacanth would be found in Indonesian waters, and thinks more discoveries of the fish in unexpected locales will occur in the future. He writes that “there is a tantalizing possibility that an unknown coelacanth is lurking off the coasts of Australia.

Raynal reminds me:

I was right about East African coelacanths populations living from Kenya to East London : now proved by catches from Malindi (Kenya), Tanzania (more than 40 specimens !), Madagascar (more than 20 specimens !), and Sodwana, (underwater films of about 20 specimens). I was right about Indonesian coelacanths. ~ Michel Raynal (2000b).

But that he has “become more cautious.”

The “the painting from Knysna (South Africa) was made several years AFTER the discovery of the type specimen.”

Raynal continues “the silver coelacanths have been studied by Fricke and Plante: neither old, nor Mexican. And the reports from the Gulf of Mexico are still too vague, they can be explained by other fishes (see Goudsward, 2020, with a chapter on this subject).”

There are surprises ahead.

While the evidence of coelacanths in Benin art may be thin, this exercise was worthwhile in demonstrating how revelations may be waiting for us in the hidden data of ethnology.

The hints are out there.

As I often say, in cryptozoology, if you don’t look, you won’t find anything.

+++

Deep appreciation and acknowledgement to Michel Raynal for consultation on aspects of the continuing search for coelacanths beyond the Indian Ocean.

+++

References Cited and Consulted.

Brentjes, Burchard. 1972. “Eine Vor-Entdeckung des Quastenflossers in Indian?”, Naturwissenschaftliche Rundschau. 25: 8, pp. 312-313.

Coleman, L. to Michel Raynal. 2020. Personal correspondence (email). September 9.

Dark, Philip J. C. 1962. The Art of Benin: A Catalogue of an Exhibition of the A.W. F. Fuller and Chicago Natural History Museum Collections of Antiquities from Benin, Nigeria. Chicago: Chicago Natural History Museum.

~ 1973. An Introduction to Benin Art and Technology. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

~ 1975. “Benin Bronze Heads: Styles and Chronology.” In African Images: Essays in African Iconology. Daniel F. McCall and Edna G. Bay, eds. Pp. 25–103. New York: Africana.

~ 1982. An Illustrated Catalogue of Benin Art. Boston: G. K. Hall.

Dark, Philip, and Matthew Hill. 1971. “Musical Instruments on Benin Plaques.” In Essays on Music and History in Africa. Klaus Wachsmann, ed. Pp. 65–78. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

De Sylva, D.P. 1966. “Mystery of the silver coelacanth.” Sea Frontiers 12: 172–175.

Ezra, Kate. 1992. Royal Art of Benin: The Perls Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Goudsward, David. 2020. Sun, Sand, and Sea Serpents. San Antonio and New York: Anomalist Books. “”Coelacanths in the Gulf of Mexico,” pp. 8 – 13.

Forman, W., B. Forman, and Philip Dark. 1960. Benin Art. [Photos by W. Forman and B. Forman; "Introduction and Notes" by Dark]. London: P. Hamlyn.

Fricke, Hans and Raphael Plante, 2001. “Silver coelacanths from Spain are not proofs of pre-scientific discovery.” Environmental Biology of Fishes 61: 461-463.

Fricke, H., O. Reinecke, H. Hofer & W. Nachtigall. 1987. “Locomotion of the coelacanth Latimeria chalumnae in its natural environment.” Nature 329: 331–333.

Handler, Jerome S. “Obituary: Philip John Crosskey Dark (1918 – 2008).” American Anthropologist, Vol. 110, Issue 4, pp. 536-545. [Republished as a SIU document.]

Kadarusman, Sugeha, H.Y., Pouyaud, L. et al. A thirteen-million-year divergence between two lineages of Indonesian coelacanths. Sci Rep 10, 192 (2020).

Luschan, F. von. 1919. Die Altertümer von Benin. Benin und Leipzig.

McCormick, Cameron. 2007. “The Case of the Silver Coelacanth,” The Lord Geekington blog. September 18.

Raynal, M. to Loren Coleman. 2020a. Personal correspondence (email). September 10.

Raynal, M. to Loren Coleman. 2020b. Personal correspondence (email). September 29.

Raynal, M. & G.S. Mangiacopra. 1995. “Out-of-place coelacanth.” Fortean Studies 2: 153–165.

Read, Charles H. and O. M. Dalton. 1899. Antiquities from the City of Benin and from other parts of West Africa in the British Museum. London: British Museum.

Thomson, K.S. 1991. Living fossil: the story of the coelacanth. Norton & Co. Inc., New York. 252 pp.

++++

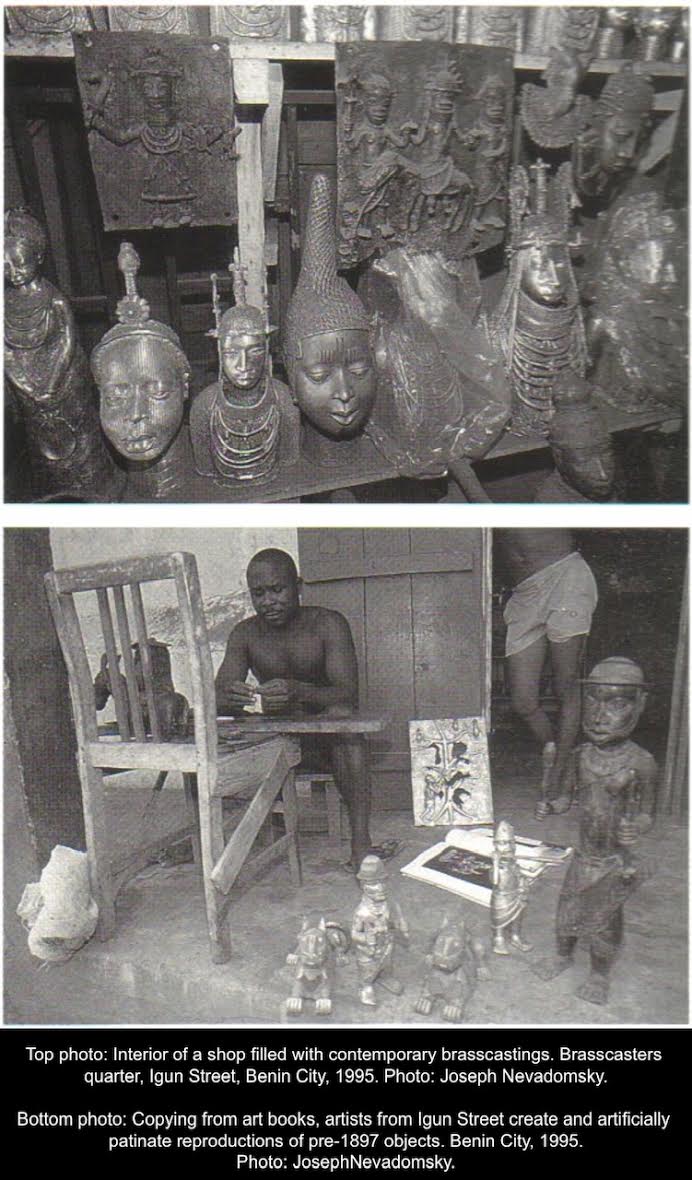

Dating of Benin art is essential, although it is embedded in the history of colonial exploitation and looting. Any “Benin Bronzes” presented without a firm pre-1897 date could be contaminated with artistic additions of modern bronze workers. “Tourist” and “eBay” art is being produced in Benin and elsewhere today. Source (see end of page). Joseph Nevadomsky. First Word: “Art and Science in Benin Bronzes.” African Arts. Spring 2004. 37 (1):1-3,86-88

[...] http://www.cryptozoonews.com/west-african-coelacanths/ [...]

Well this was interesting!