A Short History of the Shipton Snowman Track Photographs and the Tchernezky Cast

©Loren Coleman 2012

Tracks Found and Photos Taken

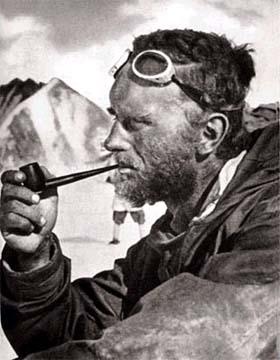

Eric Shipton (August 1, 1907 – March 28, 1977).

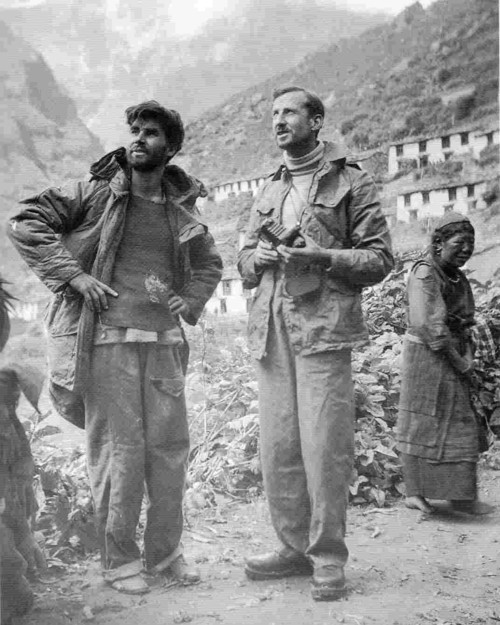

Michael Ward (March 26, 1925 – October 7, 2005; l) and W H Murray (r) at Namche Bazar, 1951 – Everest Reconnaissance expedition.

On November 8, 1951, at 4:00 pm, 1951, British mountain climber Eric Shipton, while on his fifth visit to Mount Everest, came across the tracks that would become the most famous Yeti footprints ever found and photographed. The expedition party consisted of leader Eric Shipton, Michael Ward, Bill Murray, Tom Bourdillon, Ed Hillary, Earle Riddiford, Angtharkay, Pasang Bhotia, Nima, Sen Tensing and six other Sherpas.

The discovery was made towards the end of the expedition’s time in the Himalayas, when a group of the climbers (i.e. Shipton, Ward, and Sen Tensing) were making an exploratory trek in the Gauri Sankar group to the southwest of Everest.

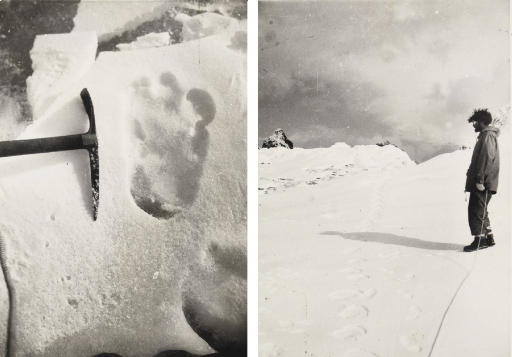

The single Yeti footprint and a series of tracks with Michael Ward, the expedition’s doctor, on the Menlung Basin. Eric Earle Shipton, Photographer.

Eric Shipton’s biographer Peter Steele (in Eric Shipton: Everest & Beyond) explains what is seen in the striking images: “Shipton took photographs of Ward standing beside the tracks. Lower down they were more distinct with sharply defined edges, twelve inches long by five wide; a big rounded toe projected slightly to one side, the second toe was separate, and the lateral three toes were smaller and grouped together. To give an idea of the scale, Shipton photographed his ice axe and Ward’s boot beside one of the prints, which appeared to have been made with a day or so….Ward, even now, says the footprints were absolutely as Shipton described them….Ward thinks that several footprints might have been superimposed on each other, as might be made by men walking in single file.” (p. 160)

Here is how Shipton talked about his finding of the footprints in his report in The Times of London: ”The tracks were mostly distorted by melting into oval impressions, slightly longer and a good deal broader than those made by our mountain boots. But here and there, where the snow covering the ice was thin, we came upon preserved impression of the creature’s foot. It showed three ‘toes’ [actually four*] and a broad ‘thumb’ to the side. What was particularly interesting was that where the tracks crossed a crevasse one could see quite clearly where the creature had jumped and used its toes to secure purchase on the other side. We followed the tracks for more than a mile down the glacier before we got on to moraine-covered ice.”

Peter Steele in his 1998 book Eric Shipton: Everest & Beyond later added [*] the “actually four,” because it has become apparent in the years since the photographs were taken that they show four, not three toes, plus the big toe. Several other authors recognize there are four, not, three digits, in addition to the hallux, adding up to five toes.

Eric Shipton’s account of the matter, from The Six Mountains-Travel Books [Pg. 621] follows: ”It was on one of the glaciers of the Menlung basin, at a height of about 19,000 feet, that, late one afternoon, we came across those curious footprints in the snow, the report of which has caused a certain amount of public interest in Britain. We did not follow them further than was convenient, a mile or so, for we were carrying heavy loads at the time, and besides we had reached a particularly interesting stage in the exploration of the basin. I have in the past found many sets of these curious footprints and have tried to follow them, but have always lost them on the moraine or rocks at the side of thc glacier. These particular ones seemed to be very fresh, probably not more than 24 hours old. When Murray and Bourdillon followed us a few days later the tracks had been almost obliterated by melting. Sen Tensing, who had no doubt whatever that the creatures (for there had been at least two) that had made the tracks were ‘Yetis’ or wild men, told me that two years before, he and a number of other Sherpas had seen one of them at a distance of about 25 yards at Thyangboche. He described it as half man and half beast, standing about five feet six inches, with a tall pointed head, its body covered with reddish brown hair, but with a hairless face. When we reached Katmandu at the end of November, I had him cross-examined in Nepali (I conversed with him in Hindustani). He left no doubt as to his sincerity. Whatever it was that he had seen, he was convinced that it was neither a bear nor a monkey, with both of which animals he was, of course, very familiar.”

Shipton and his companions moved on, but others in the expedition followed them and saw the undisturbed prints too, as Shipton mentions above.

Steele continues with more on this: “Murray and Bourdillon found the same tracks, and followed them for the better part of two miles until they were forced onto the moraine. Bourdillon, also possessing an analytical scientific mind, wrote home: ‘The Abominable Snowman is not a myth. There were about a mile of tracks set 18″ apart and staggered. The pads were 8″ by 10″ and he probably walked on 2 legs. There were impressions of the front pads where the beast had jumped a crevasse and scrabbled on landing.’ He and Murray followed the footprints for quite a way, and were impressed with the creature’s good sense of terrain in taking precisely the correct mountaineering route.” (p. 160)

Tom Bourdillon, who was also in the reconaissance party, wrote to a friend, Michael Davies about what he saw: “Dear Mick. Here are the footprint photos: sorry for the delay. We came across them on a high pass on the Nepal-Tibet watershed during the 1951 Everest expedition. They seemed to have come over a secondary pass at about 19,500 ft, down to 19,000 ft where we first saw them, and then went on down the glacier. We followed them for the better part of a mile. What it is, I don’t know, but I am quite clear that it is no animal known to live in the Himalaya, & that it is big. Compare the depths to which it & Mike Ward (no featherweight) have broken into the snow. Yours, Tom Bourdillon.” (“Yeti footprint photos go under the hammer,” by Nigel Reynolds, Arts Correspondent, The Telegraph, London, UK, September 4, 2007.)

Anthropologist John Napier remarked on the photographs being the only evidence that Shipton brought back from the Himalayas in his book, Bigfoot: The Yeti and Sasquatch in Myth and Reality (London: J. Cape, 1972): “Shipton selected what he considered was the sharpest and clearest footprint of the series and took two photographs, one with Ward’s booted foot as a scale and another with Ward’s ice-axe serving the same function. The photographs were spectacular, and so were the results of their publication. Shipton’s photographs, sharply in focus and perfectly exposed, are taken directly above the footprint. The photograph is unique, for it is the only item of evidence of the Yeti saga that offers the opportunity for critical analysis; ironically, however, it is also quite the most enigmatic.” (p.49)

Dr. Ward examines a line of tracks, 1951.

Napier also clears up one error often made in the frequent rehashing of the Shipton photos. The trail of prints taken by Shipton were never considered to have been from Yetis. Napier writes of these: “A photograph of a trail of footprints leading across a sloping, rocky, snow-covered surface towards a moraine in the middle distance has appeared in many books written on the Yeti since 1952 and has prompted a considerable amount of speculation concerning the nature of the Yeti’s gait, the length of the stride and so on. The truth of the matter, according to Michael Ward, and later confirmed by Eric Shipton, is that the trail has nothing whatever to do with the footprint. [Napier's original emphasis] The photograph was taken earlier on the same day and in roughly the same area and was probably the track of a mountain goat; it was certainly not a view of the Yeti track discovered later in the afternoon. The negatives of the trail and the footprint were filed together in the archives of the Mount Everest Foundation and, presumably, this is how the mistake arose.” (p. 49)

The track appears to be a magnet for mistakes, as we shall see in a moment. But for now, let’s be clear about one major foundation fact regarding this important track evidence found by the 1951 explorers. The expedition was looking for routes to Mt. Everest, not Yetis. They did not carry plaster or any collection materials for Yeti investigations. Plaster or concrete, furthermore, causes distortion in snow, due to the chemical reaction in the drying that releases heat. Finding these tracks was by mere chance. Photographs were all that were taken of their presence.

Researchers and historians understand the importance of this evidence.

Edward Cronin in his 1979 book, The Arun, understands the significance of these photographs: “Although the sightings must be taken on faith, the photographs of Yeti footprints contribute concrete data. The most noteworthy discovery of footprints was made by Eric Shipton and Michael Ward during the 1951 British Mount Everest Reconnaissance. The prints were made on a thin layer of crystalline snow lying on firm ice, indicating that little erosion or melting had occurred. The photographs are exceptionally clear and sharp, thus enabling definitive comparisons to be made….These photographs have since become the ‘type-specimens’ of Yeti prints.” (p. 157)

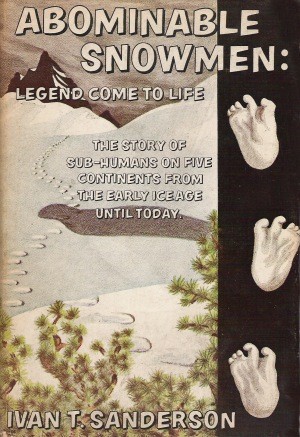

Ivan T. Sanderson, in his book, Abominable Snowmen: Legend Come to Life, published just ten years after the Shipton tracks were found, acknowledged “Eric Shipton published his photographs” and it changed the way the search for Yetis was acknowledged by the media and by academics. Sanderson noted that a “sort of revolution began within the ranks of science,” because of the Shipton photos.

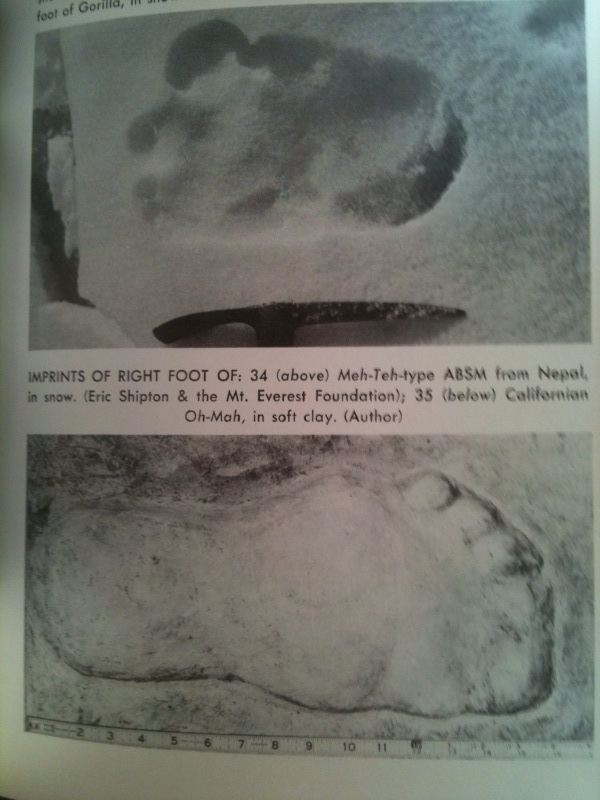

Sanderson specifically mentions the tracks in his book when looking at the evidence for the Yeti. He wrote: “1951. Eric Shipton comes across tracks on the Menlung Tsu Glacier, in the Gauri Sanka Range on the way to Everest. Photographs.”

Sanderson also shows the line drawing of the Shipton track in his appendix, captioning it: “(9) ABSM (Meh-Teh). From photo of cast made from photo of print in snow, by Eric Shipton.”

Sanderson seems to have been well aware the cast that had been produced in London, from the Shipton photos, just before his book was published, due to his contacts including Osman W. C. Hill, Bernard Heuvelmans, Odette Tchernine, and Wladimir Tschernezky. Millionaire Tom Slick brought together several of these individuals in his meetings and via his “confidential Yeti consultants” (see “Appendix C,” pp. 154-155, in Tom Slick and the Search for Yeti, Boston: Faber and Faber, 1989; revised, Craven Books, 2002).

Sanderson’s mention of the cast was specific and not in error. The caption exists in the first edition of his book (Philadelphia: Chilton, 1961), as well as in the “new revised abridgment” in paperback (NY: Pyramid, 1968) and other recent editions of Abominable Snowmen: Legend Come to Life (e.g. Kempton, Illinois: Adventures Unlimited Press, 2006; NY: Cosimo Classics, 2007).

To be clear, only photographs were taken of the track found by Shipton and Ward in 1951; no casts were secured until they were produced years later.

The photographs of these 1951 prints were immediately praised for their proof of the Abominable Snowmen of the Himalayas, and also immediately challenged in ridiculing articles. In an exhibit at the British Museum, the answer to the riddle of the new Yeti photographs was said to rest in the tracks of the languar monkey, but the tracks of the languar are much thinner and smaller.

Languar monkey tracks in snow.

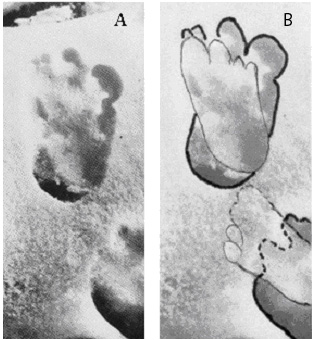

Various theories were put forward for what was found. Above in this Russian diagram on the right, double-stepping was speculated.

Not until years later, after Shipton’s death, were charges floated that Shipton pulled this off as a prank.

Steele in his biography has his say on this: “Not long ago, Peter Gillman, in the title of his piece for the Sunday Times Magazine, denounced Shipton as ‘The Most Abominable Hoaxer.” It is difficult to take seriously, being so full of scurrilous inventice. He describes Shipton as ‘mecurial and disrespectful of authority,’ ‘defiant, non-conformist, restless and embittered’; however, those who knew Shipton found him phlegmatic and dependable, tolerant and unresentful. Gilman postulates that Shipton jokingly fabricated the footprint, which he photographed together with the ice axe; but that, like the Piltdown Skull, the joke got out of hand. So, Gillman affirms, Shipton had to keep up the myth in relaliation against the Establishment that had snubbed him over the leadership of the 1953 expedition. This churlish appraisal of Shipton does little to further the story of the Yeti nor to discredit the footprints.” (p. 161)

Nevertheless, the “Shipton photograph of the clearest print became instantly famous, so much so that when Shipton arrived at Karachi Airport he was overwhelmed by reporters. This photo today is still the most important proof that the ‘Yeti’ does exist,” wrote Gian J. Quasar in Recasting Bigfoot (Lexington, Kentucky: Brodwyn-Moor & Doane, 2010, p. 39).

Cast Constructed

In analyzing the Shipton Yeti photographs, it became apparent to some researchers that one of the limitations were the photographs themselves. They were two-dimensional and anthropologists and zoologists wanted to see them three dimensionally. A representation of what the foot of the animal that made the print looked like needed to be made. Since no cast of the Shipton/Ward/Tensing find had been taken, the only knowledge of the unknown animal that made it was the photographs of the found print. Therefore, one scientist stepped forward to make the cast that was shared within the small fraternity of Yeti investigators existing in the decade after the Shipton find.

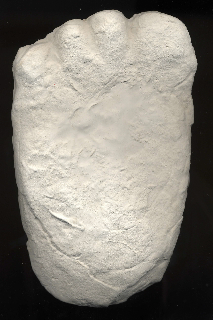

A Russian zoologist living in London decided to do something about this dilemma. That person was Wladimir Tschernezky of the Zoology Department, Queen Mary College, Mile End Road, London, United Kingdom. As he explained in a contribution to Nature 186, 496-497 (7 May 1960): “The clearness of the tracks of the ‘Snowman’ shown in the photograph taken by Eric Shipton has enabled me to make a reconstruction of its foot. This has been used to produce imprints in snow which show a great similarity to the natural tracks, suggesting that the model is accurate.”

Tschernezky’s created cast, the apparent first one made from the Shipton cast, was detailed in Nature in “A Reconstruction of the Foot of the ‘Abominable Snowman’.”

One of the better records of the making of Tschernezky’s cast and the respect it was given among Abominable Snowmen researchers is contained in Odette Tchernine’s The Snowman and Company (London: Robert Hale, 1961). Tchernine, a Russian herself living in London, interviewed Tschernezky about his research. She quoted him as saying, “The greatest service that Shipton has given the world is not found in his impressive and valuable mountaineering experiences, and his reconnaissance of Everest, but is found in these photographs he took of the Snowman’s tracks. And time will prove my words.” (pp. 102-103)

Tchernine wrote: “During different periods of leave from his [Tschernezky's] regular work he had experimented with one of the footprint photographs taken by Eric Shipton on the Menlung Glacier in 1951. This was enlarged to actual size, and he experimented with a plaster cast he made according to the structure shown in the print.”

Tschernezky detailed what he found in his reconstructions: “The Snowman footprints photographed by Eric Shipton preserved certain particular details, such as imprints of each toe and the small snow partitions separating them. That proves that the track was not deformed through melting. So it is possible to establish the systematic position of this mysterious creature experimentally.”

“Moulded on Shipton’s photograph of the footprint enlarged to its nature size, I modelled a plaster cast of the foot (Figure C in my new photographs). I established the correctness of the artificial model by producing an artificial track from it on snow (crushed ice). I then compared the result with the original, natural-size photographs of the footprint in the actual snow. The similarity is revealing.” Tschernezky revealed to Tchernine.

While Tschernezky’s name was formally published as “Wladimir” in Nature, Tchernine gave his name as the phonetic ”Vladimir,” as she used in her book’s Chapter Ten title, “Vladimir Tschernezky’s Experiments.”

In an editorial in the New Scientist, May 12, 1960, it is noted that Mr. W. Tschernezky, a technician in the Zoology Department at Queen Mary College, writes in Nature that he “painstakingly reconstructed in plaster the foot which made Mr. Shipton’s print.” The New Scientist writer says that “Tschernezky has convinced me that the Snowman must be taken seriously. The Shipton footprint, as he shows, is markedly different from those made by men, gorillas, languars or the Himalayan black bears. The New Scientist author is intrigued by Tschernezky’s notion that the Yeti might be a surviving Gigantopithecus: “The idea of a sort of land-based coelacanth, a living fossil skulking in the mountains of Tibet, takes the whole concept of the Snowman out of the science fiction category.”

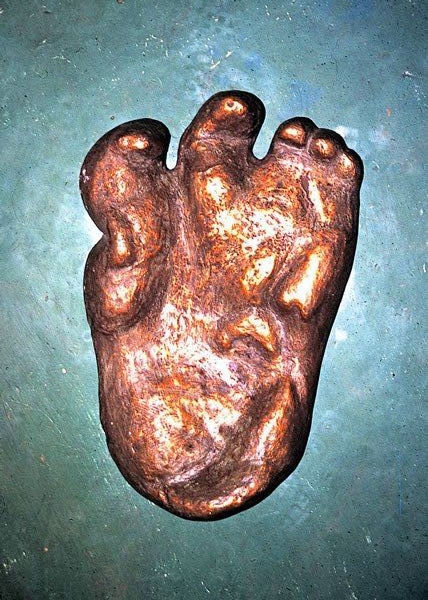

Reconstruction of Meh-Teh by W. Tschernezky, 1957

Tschernezky would discuss this cast again in the January 1975 issue of The Mankind Quarterly (pp. 163-177), in his paper “The Unpublished Tracks of Snowman or Yeti” by W. Tschernezky and C.R. Cooke.

“Tschernezky even went to the trouble of making a plaster cast of the image in the Shipton Photo and testing its function,” wrote Gian J. Quasar. In his Recasting Bigfoot (San Francisco: Brodwyn-Moor & Doane, 2010), Quasar uses a drawing (above) of Tschernezky’s cast throughout his book, and labels it correctly, “This shows the left foot from the bottom.”

This is an important part of the reality of this track that becomes revealing in detailing one of the most common mistakes today associated with the track and later casts.

Cast Mistakes Muddle the Mix

Ivan Terence Sanderson (January 30, 1911 – February 19, 1973) was a naturalist and writer born in Edinburgh, Scotland, who became a naturalized citizen of the United States. Sanderson is remembered for his nature writing, television appearances, and his interest in cryptozoology and Fortean subjects. He was my mentor, a friend, and I respect his work. But Ivan was only human, and part of what he left behind has been in error. His legacy lives on in a few mistakes that have become factoids thought to be correct by his followers, including ones regarding the Shipton photographs and the Tchernezky cast.

How did this happen? Sanderson founded the Ivan T. Sanderson Foundation in August 1965 on his Blairstown, New Jersey property, which became the Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained (SITU) in 1967. SITU was a non-profit organization that investigated strange phenomena ignored by mainstream science. I was an early member, and later an honorary one. I do not wish to discredit any of the fine work done by Ivan, or any of the other members of SITU. But sometimes, little errors can become overblown.

“Assisting him in his research was his nonprofit organization, Society for the Investigation of the Unexplained, or SITU, made up primarily of renegade scientists, researchers, adventurers, strange geeky characters and other interested parties who had helped him investigate and compile information on unusual creatures, artifacts and phenomena found throughout the world,” wrote Sanderson biographer Richard Grigonis.

SITU produced a newsletter that was neither a peer-reviewed journal nor frequently a well-edited publication. It was often a collection of thoughts of Sanderson’s, other staff, and visitors, and was known as Pursuit for most of its existence.

In one issue of Pursuit, from July 1971, it has been incorrectly assumed that “Sanderson” said there was a cast made by Shipton in the field. Let me deconstruct what occurred, and straighten out the record.

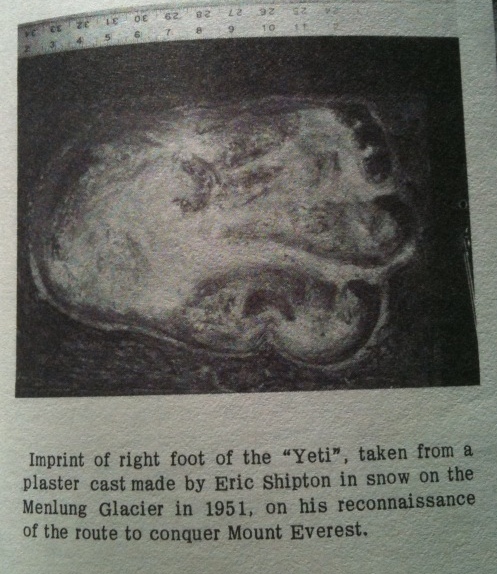

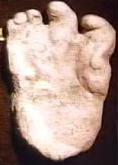

A caption was placed at the bottom of a photograph in Vol. 4, No. 3 of Pursuit, reading “Imprint of right foot of ‘Yeti’, taken from a plaster cast made by Eric Shipton in snow on the Melung Glacier in 1951, on his reconnaissance of the route to conquer Mount Everest.”

The caption had a series of errors. First off, it was not written by Ivan T. Sanderson. Second, it is the imprint of a left foot alleged of the Yeti, not a right foot. And third, the plaster cast was not made by Eric Shipton “in snow.” We know that no casts were made in 1951 by Shipton or anyone else on that expedition.

This photo caption is from a book review by Marion L. Fawcett, not by Sanderson. She apparently placed the photograph with her review and then made the mistakes in the caption.

One of the most frequent mistakes made in dealing with the footprint photographs of the Shipton track is to misread it as being made by a right foot, when, in fact, the Shipton-found track was of a left foot.

Just because something is in print in Pursuit does not make it a reality or a correct piece of information. No casts were made by Shipton, Ward, or anyone else on the 1951 expedition. A plaster cast of the Shipton photo was made later by Tchernezky and then copies of that made. The caption on the photograph is in error, and the general sloppiness of the editing of this Pursuit belies the caption on this Shipton cast sharing helpful information.

What is shown is a construction where the void would appear to be as the footprint had been made but, unfortunately, with a caption with the wrong information. Indeed, you only have to look as far as the next photograph over to see the same kind of mistakes being made.

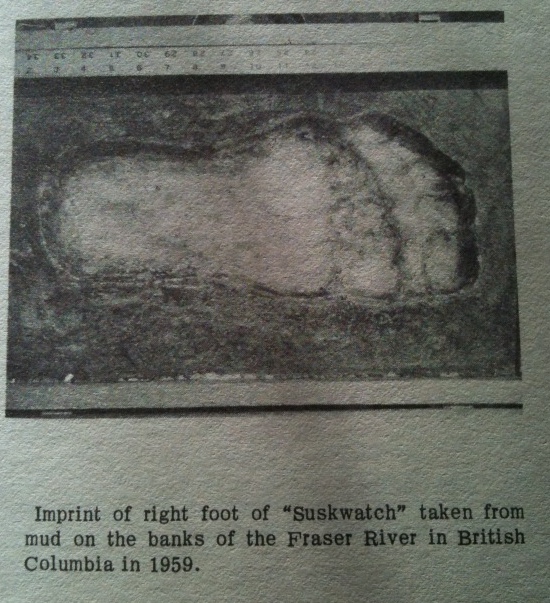

Next to the “Yeti” imprint is shown what is described in the caption as, “Imprint of right foot of ‘Suskwatch’ taken from mud on the banks of the Fraser River in British Columbia in 1959.”

This caption is rather melodramatic, using the term “Suskwatch,” but it is also as fictional or incorrect in its information as the one showing the “Yeti” imprint.

Once again, what is show is the left foot imprint, not a right foot. This is a block of plaster with a left foot imprint in it of a Bigfoot that Sanderson was known to have taken around to television programs.

The original print does not match any 1959 track found in British Columbia. Marion L. Fawcett allegedly has added an incorrect caption to this photograph too.

This photo actually instead is an exact match for the 1959 Bluff Creek, California, left foot imprint that Ivan T. Sanderson has in his 1961 Abominable Snowmen: Legend Come to Life at Plate No. 35, shown below, individually and from the book.

35 (below) Californian Oh-Mah, in soft clay. (Author)

Abominable Snowmen: Legend Come to Life

The copy in metal of the Shipton track photo cast (again the left foot) was owned by Ivan T. Sanderson, and hung on the walls of the Society of the Investigation of the Unexplained, Blairstown, New Jersey. Irregularities in the sole of the print reflect those placed there to copy what was found in the Shipton photographs. (Photo circa 1969 courtesy Richard T. Grybos.)

This photograph shows another Shipton photo-created cast housed at SITU’s headquarters in the mid-1970s. Photo credit: Richard Grigonis.

SITU personnel made mistakes in identifying a copy of this above cast, as I mentioned in an earlier posting, when in 1980 John A. Keel showed a mirror copy of this on the David Letterman show and said it was from a “Bigfoot in New Jersey.” Not Bigfoot. Not New Jersey.

The above is a cast of an “unknown” creature footprint at SITU. “Some of the footprint casts collected by SITU were so unusual or ill-defined that it was impossible to even speculate on what made them, such as this one,” noted Richard T. Grybos.

But here is another SITU cast that I can correctly identify. What is shown above from the Sanderson/SITU collection is a copy of the Tom Slick Yeti cast that was taken in Nepal, as the track was found in mud. Below is the photo of the original one. Also the other photo is a copy of the Slick cast in my own collection. This cast may hold a clue to how the other ones arrived at SITU. I would speculate that Sanderson’s copies were obtained from Tchernezky, or, due to the fact Sanderson had a Slick Yeti cast, perhaps via Slick.

Left versus Right

Eric Shipton took photographs. None of the Sherpas, porters, Michael Ward, or Shipton cast any track from the single print or the trackway in plaster, cement, or any substance. They took photographs only. The creation of casts occurred afterward, and there is absolutely nothing in the record stating otherwise.

What has occurred in the years since, though minor careless editing at SITU and plaster copy makers’ errors, has merely compounded the problem.

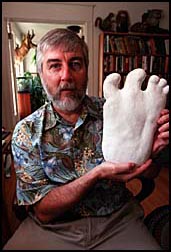

Below you can see I am holding the properly configured cast of the left foot that goes with the left foot track in the Shipton photos. Sanderson’s metal cast, white plaster copy, and negative imprint all match the original left foot Shipton track photographs, after which they were modelled. Their origins may be linked directly back to Tchernezky.

The 1951 Shipton print’s cast has today been shared among several researchers worldwide. It is a frequent and useful artifact among cryptozoologists in the 21st century. But some cast makers are selling copies of a right foot copy that is a total creation based upon how the Shipton photograph appears – and they are making the mistake that the front-on-view is how a Shipton cast should appear. These are new reconstructions thus do not even match the track because they are actually flipped, as seen below.

Different opinions exist in the world of Abominable Snowmen history, and everyone is welcome to their sense of the events of 60 or 40 or 20 years ago. But one thing is certain, the Eric Shipton photographs of the alleged Yeti track of 1951 live on and still stimulate passionate feelings among investigators, debunkers, skeptics, and historians. If we can calmly study them, we may learn more from them.

As John Napier said, the 1951 Yeti track image, due to Shipton’s photography, “is unique, for it is the only item of evidence of the Yeti saga that offers the opportunity for critical analysis.”

©Loren Coleman 2012

Follow CryptoZooNews

Not Found

The resource could not be found.