“For books by relatively unknown authors, bad reviews caused sales to rise, by an average of 45%.” ~ Jonah Berger, “Bad Reviews Can Boost Sales. Here’s Why,” Harvard Business Review, March 2012.

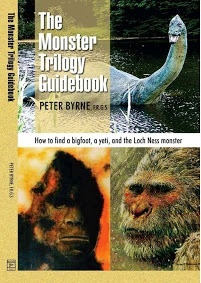

Several writers of blog and early articles have heaped praise on Peter Byrne’s forthcoming book, calling him “awesome” and the book ”greatly anticipated.” But it seems none of these early “reviewers” have actually read the book, or even some of the passages already being shared online by the publisher, Hancock House. I have examined what is available and I have some grave concerns. Of course, as the quotes above indicate, critiques like mine won’t hurt Byrne’s sales. Such reviews merely alert people to the book, and those readers will buy it no matter what is written about it.

In Peter Byrne’s new book, according to the shared release of one section of the volume, the author again retreads his jumbled history of the naming of the “Abominable Snowman.” It is a story that is incorrect, and needs to be highlighted as a cautionary view of what may be in store for readers looking for his view of cryptozoology in the rest of his new “guidebook.” Byrne tells tales from his memory, it appears, as a matter of record. John Green and others are aware of that, as many of us have learned. This is unfortunate, for some people listen to Byrne and give accord to his opinions. But his memory is often faulty, as for example, in the case I will discuss today.

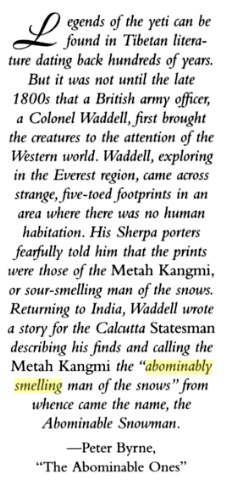

Here is the specific passage in Bryne’s new book (from Chapter 18, “Yeti Hunter”) to which I point for this critique:

The first Westerner to report the presence of a large unidentified primate in the Himalaya was the nineteenth century high-mountain British trekker, Colonel Waddell. One day, while high in the central Nepal ranges, he came across a set of big, wide, humanlike foot- prints with five toes and set in a pattern that suggested whatever made the prints was bipedal (walked upright on two legs). When he asked his Sherpa porters what made the prints they told him they were made by the metah kangmi. The words metah and kangmi are Tibetan. Metah means bad smelling or foul smelling, and kangmi means man of the snows, or snowman. A little later, after returning to India, Waddel wrote a short article for the Calcutta Statesman in which he described his find. He called the creature that made the prints the “abominably smelling man of the snows,” in accordance with what his Sherpas had told him. From this article, in time, came the name abominable snowman, and this is the name that we used when I was young.

For example, in Travelers’ Tales Nepal, edited by Rajendra S. Khadka (Redwood, CA: 1997: p. 97), a passage from a work credited to Peter Byrne is quoted:

In that year an incident occurred that was impressive enough but which might have been either wholly or temporarily buried had it not been for a concatenation of almost piffling mistakes. In fact, without these mistakes it is almost certain that the whole matter would have remained in obscurity and might even now be considered in an entirely different light or in the status of such other mysteries as that of “sea-monsters.” This was a telegram sent by Lt. Col. (now Sir) C. K. Howard-Bury, who was on a reconnaissance expedition to the Mt. Everest region.

The expedition was approaching the northern face of Everest, that is to say from the Tibetan side, and when at about 17,000 feet up on the Lhapka-La pass saw, and watched through binoculars, a number of dark forms moving about on a snowfield far above. It took them some time and considerable effort to reach the snowfield where these creatures had been but when they did so they found large numbers of huge footprints which Colonel Howard-Bury later stated were about “three times those of normal humans” but which he nonetheless also said he thought had been made by “a very large, stray, grey wolf.” (The extraordinarily illogical phrasing of this statement will be discussed later on, but it should be noted here that a large party of people had seen several creatures moving about, not just “a wolf,” and that it is hard to see how the Colonel could determine its color from its tracks.) However, despite these expressions, the Sherpa porters with the expedition disagreed with them most firmly and stated that the tracks were made by a creature of human form to which they gave the name Metoh-Kangmi.

Colonel Howard-Bury appears to have been intrigued by this scrap of what he seems to have regarded as local folklore, but, like all who have had contact with them, he had such respect for the Sherpas, that he included the incident in a report that he sent to Katmandu, capital of Nepal, to be telegraphed on to his representatives in India. And this is where the strange mistakes began. It appears that Colonel Howard-Bury in noting the name given by the Sherpas either mistransliterated it or miswrote it: he also failed to realize that he was dealing with one of several kinds of creatures known to the Sherpas and that they, on this occasion, apparently both in an endeavor to emphasize this and for the sake of clarity used as a generic term for all of them, the name kang-mi, which was a word foreign to their language. This is a Tibetan colloquialism in some areas, and is itself partly of foreign origin even there, in that kang, is apparently of Chinese origin while mi is a form of Nepalese meh. The combination thus meant “snow creature.” His metoh would better have been written meh-teh, a name of which we shall hear much, and which turns out to mean the meh or man-sized tehor wild creature. However, the Indian telegraphist then got in the act and either he dispatched this word as, or it was transcribed in India, as metch.

The recipients in India were unfamiliar with any of the languages or dialects of the area but they were impressed by the fact that Howard-Bury had thought whatever it might be, important enough to cable a report, so they appealed to a sort of fount of universal wisdom for help. This was a remarkable gentleman named Mr. Henry Newman who has for years written a most fascinating column in the Calcutta Statesman on almost every conceivable subject and who has the most incredible fund of information at his finger tips. This gentleman, however, did not really know the local languages or dialects of eastern Tibet and Nepal either, but this did not deter him from giving an immediate translation of this metch kangmi which, he stated categorically, was Tibetan for an “abominable snowman.” The result was like the explosion of an atom bomb.

Nobody, and notably the press, could possibly pass up any such delicious term. They seized upon it with the utmost avidity, and bestowed upon it enormous mileage but almost without anything concrete to report. The British press gulped this up and the public was delighted. Then there came a lull in the storm. During this time, it now transpires, a number of eager persons started a fairly systematic search for previous reports on these abominable creatures, and they came up with sufficient to convince their editors that the story was not just a flash in a pan, but a full-fledged mystery that had actually been going on for years.

Wikipedia also summarizes what occurred (with reams of references and sources):

The appellation “Abominable Snowman” was coined in 1921, the same year Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Howard-Bury led the joint Alpine Club and Royal Geographical Society ”Everest Reconnaissance Expedition” which he chronicled in Mount Everest The Reconnaissance, 1921. In the book, Howard-Bury includes an account of crossing the “Lhakpa-la” at 21,000 ft (6,400 m) where he found footprints that he believed “were probably caused by a large ‘loping’ grey wolf, which in the soft snow formed double tracks rather like a those of a bare-footed man”. He adds that his Sherpa guides “at once volunteered that the tracks must be that of ‘The Wild Man of the Snows’, to which they gave the name ‘metoh-kangmi’”. ”Metoh” translates as “man-bear” and “Kang-mi” translates as “snowman”.

Confusion exists between Howard-Bury’s recitation of the term “metoh-kangmi” and the term used in Bill Tilman’s book Mount Everest, 1938 where Tilman had used the words “metch”, which does not exist in the Tibetan language, and “kangmi” when relating the coining of the term “Abominable Snowman”. Further evidence of “metch” being a misnomer is provided by Tibetan language authority Professor David Snellgrove from theSchool of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London (ca. 1956), who dismissed the word “metch” as impossible, because the consonants “t-c-h” cannot be conjoined in the Tibetan language.” Documentation suggests that the term “metch-kangmi” is derived from one source (from the year 1921). It has been suggested that “metch” is simply a misspelling of “metoh”.

The use of “Abominable Snowman” began when Henry Newman, a longtime contributor to The Statesman in Calcutta, writing under the pen name “Kim”, interviewed the porters of the “Everest Reconnaissance expedition” on their return to Darjeeling. Newman mistranslated the word “metoh” as “filthy”, substituting the term “abominable”, perhaps out of artistic license. As author Bill Tilman recounts, “[Newman] wrote long after in a letter to The Times: The whole story seemed such a joyous creation I sent it to one or two newspapers’”. Source.

The record is clear that Waddell is part of the early history of the Yeti, but he has nothing to do with the naming of the “Abominable Snowman”:

An early record of reported footprints appeared in 1899 in Laurence Waddell’s Among the Himalayas. Waddell reported his guide’s description of a large apelike creature that left the prints, which Waddell thought were made by a bear. Waddell heard stories of bipedal, apelike creatures but wrote that “none, however, of the many Tibetans I have interrogated on this subject could ever give me an authentic case. On the most superficial investigation it always resolved into something that somebody heard tell of.” Source.

Therefore, the breakdown is thus:

Lieutenant-Colonel Laurence Waddell was one of the first Europeans to see tracks which were tied to being Yeti, in 1899. They were not mentioned in the India media, and the unknown beast making them was identified as a creature that was not called an “abominably smelling man of the snows.” That phrase never actually was used as part of the story of the naming of the Abominable Snowman, except by one individual: Peter Byrne.

Instead, Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Howard-Bury saw actual living forms at a distance, in 1921 (not 1899, as Byrne states), which were identified by his Sherpas as Metoh-Kangmi (not “metah kangmi” as Peter Byrne writes).

Waddell, which Byrne states was the author of the mistakes in the article in India, was not the writer of the news dispatches. It was Henry Newman at the Calcutta Statesman. Byrne did, at least, get the correct newspaper name.

The misnaming of the “Abominable Snowman” is a complex enough story, as it is, without Peter Byrne continuing to complicate the matter by constantly compounding the mistakes with his own creations about “abominably smelling man of the snows,” when odor never came into the picture!

The book is not coming out until sometime late in May. Perhaps the editors at Hancock can go back in and clean up the historical errors in this “guidebook.” Maybe they could have it proofread by some people that actually know the history of cryptozoology, and not just let Peter Byrne’s memory dictate the “facts.”

I look forward to reading the entire book, and seeing where Byrne goes with the rest of his literary journey in his hunt for Yeti, Bigfoot, and Loch Ness Monsters.

Some people are reprinting this entire blog.

That’s copyright infringement.

If you wish to note these writings, please ask for permission to briefly quote from the

essays and then link back to them, so a complete

understanding of the discussions will be intact. Thank you.

Follow CryptoZooNews

Not Found

The resource could not be found.