The International Cryptozoology Museum understands that indigenous peoples have had masks removed from their culture. Some of these masks have represented their groups’ thoughts on unknown hairy hominoids. Here are a few examples from a book’s cover, from totem representations, and masks.

(Museums today tend to collect and display contemporary masks made by Asian artists, and modern Canadian First Nations and American Native artists.)

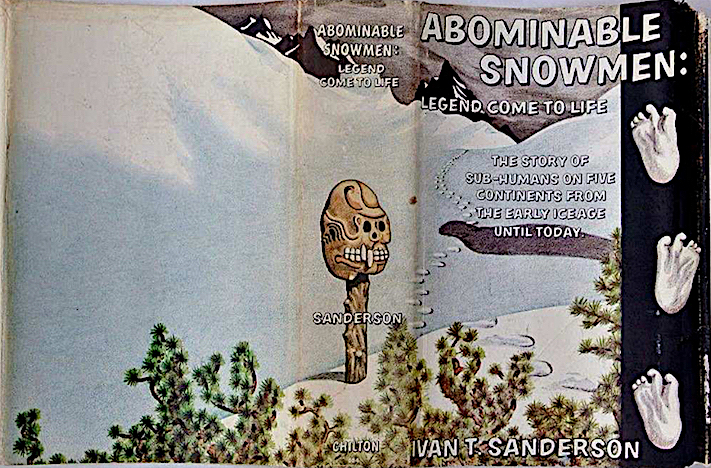

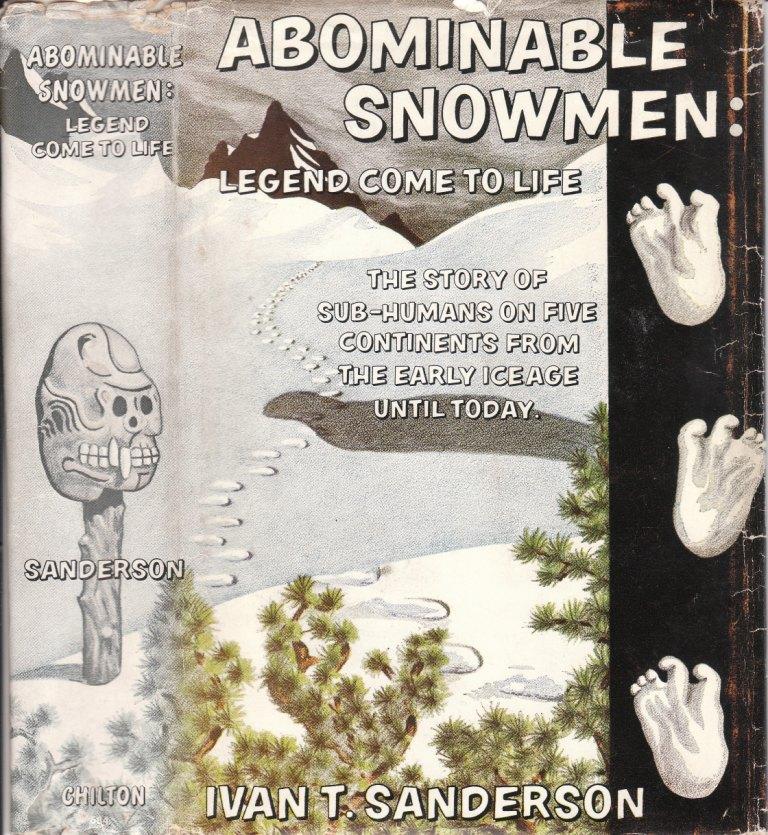

Abominable Snowmen: Legend Come To Life by Ivan T. Sanderson (1961). Cover image credit: Christopher Murphy.

Dust jackets nearing 60 years old result in faded colors of important details.

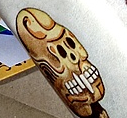

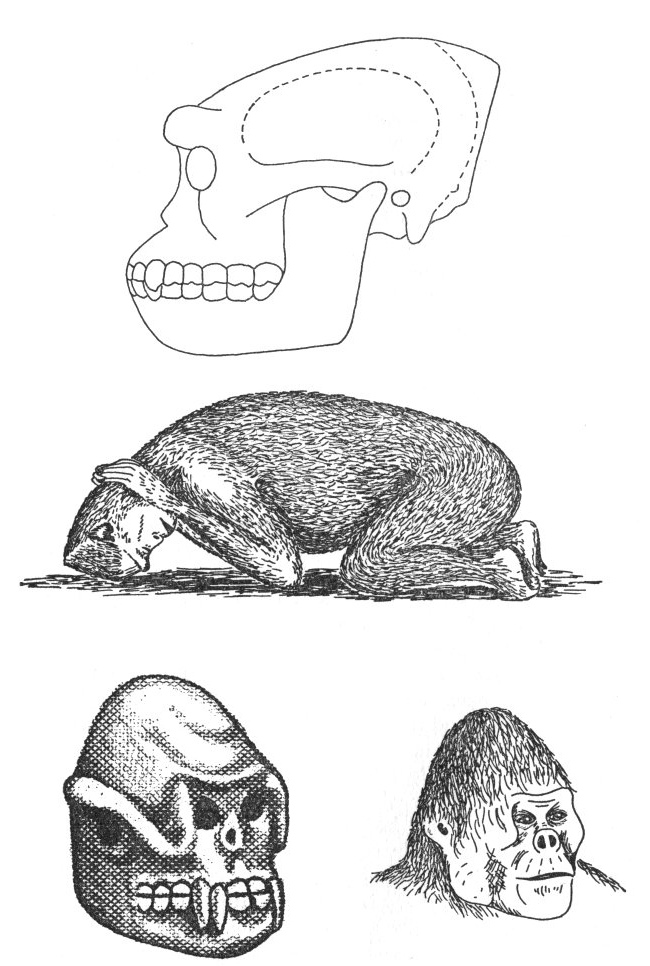

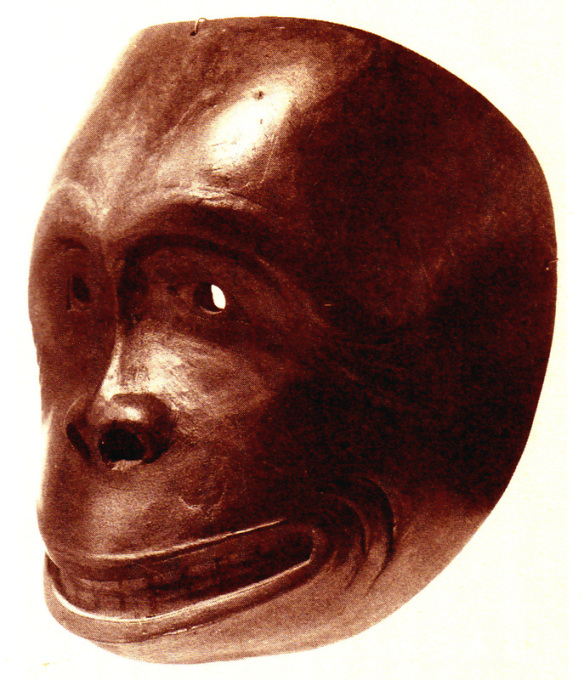

Ivan T. Sanderson created the cover of his 1961 book to reflect what was known about the “Abominable Snowmen” of the world. One visual example he tried to capture was a carved mask recently (at the time) in the news, on the spine of the cover. In the British publication, The Observer, Richard Fitter had written an article “Mask Provides New Clues to Snowman,” on October 23, 1960. It seems Sanderson saw the article as he was designing the final stages of the art as the book went to press. We know the events of 1960s ~ Hillary’s debunking expedition and news articles ~ influenced him greatly. Sanderson’s cover painting was based on an ancient mask from Mongolia, researched by Russian scientists.

The Old World

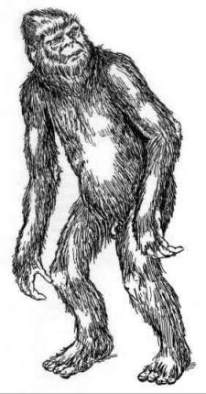

Mongolian Almas, drawn by Harry Trumbore, from descriptions for The Field Guide to Bigfoot and Other Mystery Primates by Loren Coleman and Patrick Huyghe (Anomalist, 2006).

(Top) Hypothetical skull of the Ksy-Giik type of Abominable Snowman as reconstructed by Russian scientists.

(Center) A drawing made by Prof. Khakhlov of the Almas type of Abominable Snowman from native descriptions.

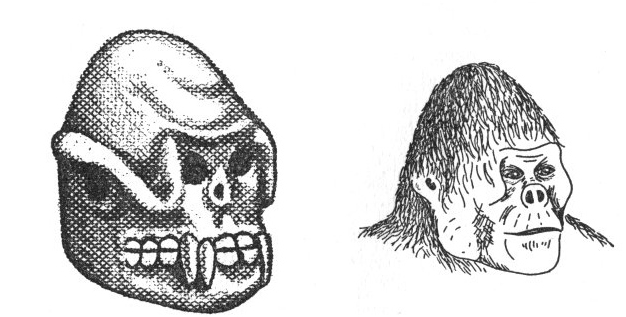

(Bottom, left) An ancient mask from the great Mongolian plateau.

(Bottom, right) Reconstruction of head and face of the creature on the mask, drawn by Russian scientists.

The New World

Sasquatch/Bigfoot/Hominology researchers have found that most Pacific Northwest wood carvings (masks and totem poles) depicting the Sasquatch are those of the Kwakiutl Tribe in British Columbia, Canada. The carvings depict either the female Sasquatch which has long hair and whistling lips, or the male which has no hair and a straight, open mouth with exposed teeth. The female is called D’sonoqua (several spellings and a proper noun). The male is called a buck’ was, or merely buckwas (not a proper noun). The interpretation is either “wild woman of the woods,” or “wild man of the woods,” as applicable.

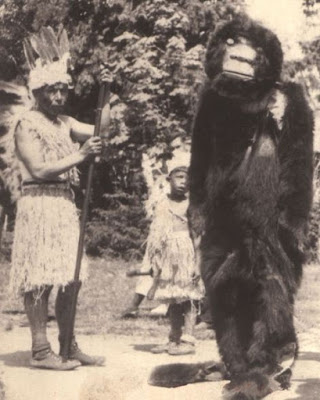

Second photo from 1938 Sasquatch Days Festival.

A Sasq’ets mask, commonly know as Sasquatch, is seen in this undated handout photo. Bigfoot sightings may be elusive, but a Sasquatch mask missing for 75 years was easily found after a simple request from a British Columbia First Nation. THE CANADIAN PRESS/ HO, Museum of Vancouver (May 14, 2014)

Hunting for an elusive sasquatch mask revered by a British Columbia First Nation has been a 16-year journey for James Leon, taking him through London, Boston, New York and Ottawa.

In the end, all it took was a question to the lady sitting next to him at a Vancouver event that led him to his nation’s Sasq’ets mask that vanished 75 years ago.

Leon was at a repatriation event for another First Nations artifact held by the Vancouver Museum when he asked the lady sitting beside him if she knew of the ape-like mask partially covered in bear fur.

“Her eyes lit up and she said ‘We were just looking at that mask the other day.’ And they were gracious enough to go get it for me,” he said with a chuckle.

The mask disappeared in 1939 from Sts’ailes First Nation, near Harrison Hot Springs in B.C.’s Fraser Valley.

Community elders told Leon that the mask had been taken by J.W. Burns (pictured), a teacher at the Chehalis Indian Day School, and a man obsessed with the Sasquatch legend.

Burns, who is often credited for bringing the word “Sasquatch” into common use, donated the mask to the Vancouver Museum.

Leon took the job of finding the mask seriously and learned it had been on travelling display. He searched through the archives of several museum’s known for having artifacts from British Columbia.

While all those elders are gone, he said they’d be pleased the mask has been returned.

“We do burning for the Sasquatch. It’s our belief that his primary role is to ensure that the land is being taken care of. Because everyone of us, as Sts’ailes people, we carry an ancestral name, a rich name from the land.”

Museum of Vancouver CEO Nancy Noble said musuems have a social and cultural obligation to consider repatriating certain objects from their collections to First Nations.

“For aboriginal peoples, the return of an object with significant cultural or spiritual value can help to rebuild awareness, educate youth and strengthen ties to a culture that was often suppressed or taken away,” Nobel said in a news release.

The mask was carved by Ambrose Point based on stories “from the beginning of time.”

While the more recent stories of bigfoot are enough to produce nightmares, Leon said his people consider spotting a sasquatch good luck.

“There are certain things that happened to us when we see one,” he said. “They call it gifts that come with seeing one, like I’d be a good speaker or a good hunter.”

There’s an even better endowment — a golden gift — if the Sasquatch sees you, he explained.

Leon said his closest encounter to a real sasquatch came many years ago when he was walking with his then-wife.

“She kind of pushed me aside, so I didn’t see it because I wasn’t ready for the gift that comes with it.”

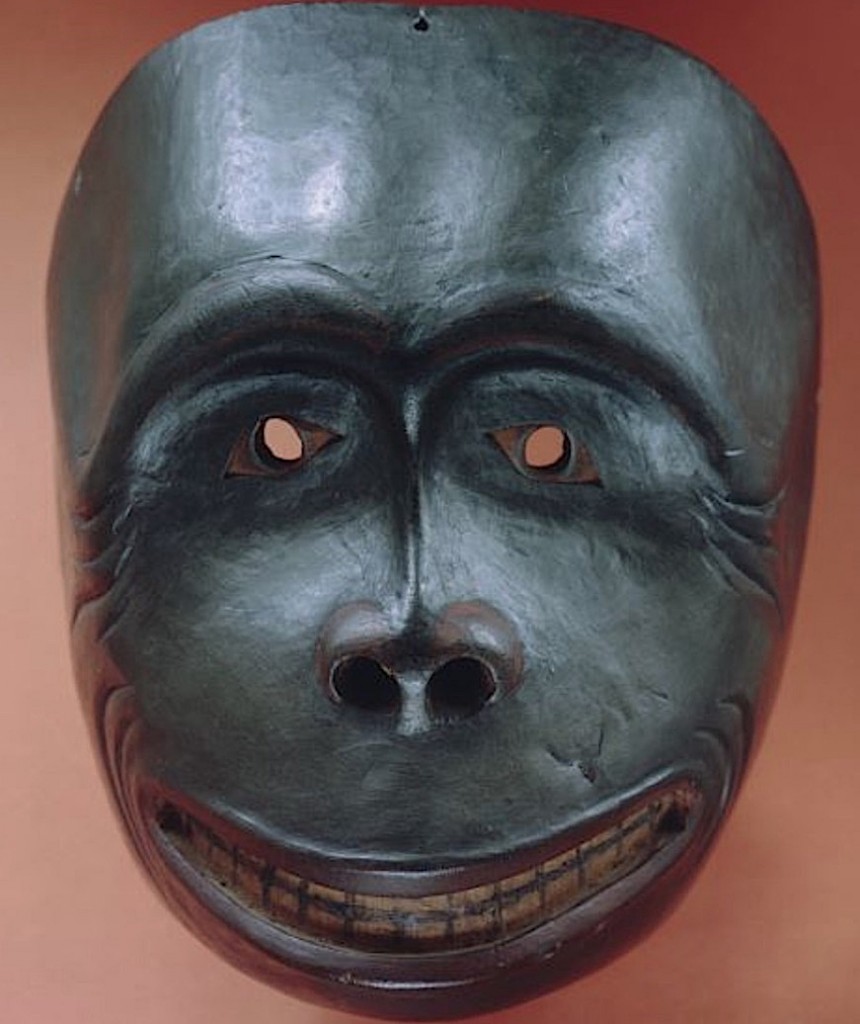

However, the most ape-like mask ever found was one fashioned by a member of the Tsimshian First Nation, also of British Columbia. This mask was made in about 1850 or before, and invites considerable speculation as to what inspired the artist to create it.

I saw this artifact on display at the Peabody Museum, in the 1970s.

From the artifact description in Cambridge, Massachusetts:

“Bigfoot” in the Peabody: Tsimshian Mask

“Bigfoot” in the Peabody: Tsimshian Mask, ca. AD 1860, Tsimshian Indian, Northwest Coast, North America, PM 14-27-10/85877

This beguiling monkey mask was hewn from red cedar around 1869 by the Niska branch of the Tsimshian Indians of Canada’s North West coast. The best and earliest example of its kind, this particular mask realistically captures a likeness to eyewitness descriptions of the enigmatic Bigfoot. Similar, more stylized monkey masks, were also worn by other tribes during mimed dances that portrayed the actions of what might be described as a Sasquatch. C.S.C.

The initials “C.S.C” are for anthropologist Carleton S. Coon, who wrote an article about this mask for Harvard magazine. I interviewed Coon at his Gloucester home about his involvement with the Tom Slick expedition, and his work with Sanderson, Slick, Peter Byrne, and others.

When the museums open again, be certain to carefully examine the not-so-abominable masks.

[...] the believers. Who do you trust? Well, someone like Loren Coleman is a great start. His report on Not-So-Abominable Masks makes a compelling argument that these carvings by the Indigenous peoples are more than their [...]

[...] the believers. Who do you trust? Well, someone like Loren Coleman is a great start. His report on Not-So-Abominable Masks makes a compelling argument that these carvings by the Indigenous peoples are more than their [...]