Cryptozoologist of 2011: Mark Murphy

by Loren Coleman, Director, International Cryptozoology Museum

Cryptozoology is the study of unknown or hidden animals. The scope of this science, needless to say, is more than doing fieldwork and finding new species. Sometimes cryptozoology is concerned with recovering records and histories, and therefore takes place among old records, basements, libraries, and archives. This year we celebrate the discoveries of one such cryptozoological figure.

Archive researcher Mark Murphy visits the International Cryptozoology Museum in 2011.

During the late summer of 2011, reports swept through the mainstream media and social media of newly unearthed State Department documents discussing a specific cryptid, the Yeti. The story went viral. The remarkable find made the “Google Editor’s Pick.” One posting told of this as coming “Straight from the National Archives.” The story appears to have broken initially after being highlighted by Paul Bedard and Lauren Fox in U.S. News & World Report on September 2, 2011. It overwhelmed the alternative, web, and other news sources for days, and may be the reason behind some Yeti movies you might see in 2013.

The discovered papers confirmed for the first time the United States government’s belief that the Abominable Snowmen or Yetis roamed the mountains of Nepal in the 1950s, a finding that shocked federal officials “including the archivist who discovered the papers,” noted U.S. News.

That archivist, Mark Murphy (above), is our “Cryptozoologist Of The Year” for 2011.

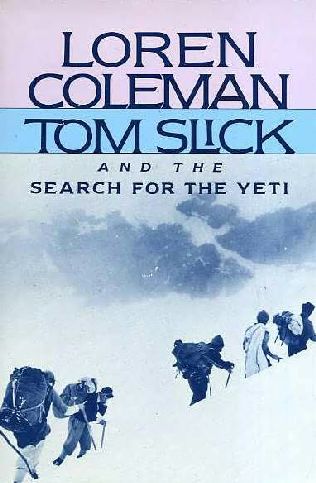

Mark Murphy examines the International Cryptozoology Museum’s Tom Slick expedition materials. Murphy would donate copies of unclassified documents he discovered in the National Archives to the museum.

Long written off as merely an unfounded legend—it was never caught or photographed—the documents provided by the National Archives show that officials in the State Department, Foreign Service, and U.S. Embassy in Kathmandu, Nepal, not only believed in “Yeti,” but endorsed rules for American expeditions to follow when hunting the unknown hairy hominoids down.

“There are, at present, three regulations applicable only to expeditions searching for the Yeti in Nepal. These regulations are to be observed,” said a memo from the embassy written on State Department letterhead.

The first rule required that expeditions buy a permit. The second demanded that the beast be photographed or taken alive. “It must not be killed or shot at except in an emergency arising out of self defense,” wrote Embassy Counselor Ernest Fisk on November 30, 1959. And third, any news proving the existence of the Abominable Snowman must be cleared through the Nepalese government which probably wanted to take credit for the discovery.

The closer and closer the archivist looked, he became startled at what he was reading and thus revealing.

Archivist Mark Murphy said he couldn’t believe his eyes when he discovered the long-ignored papers written at the end of the Eisenhower administration. “I thought I was seeing things,” he said. “These documents show that finding the Yeti was a big deal in the 1950s. It goes to show the government was taking this seriously.”

“How seriously?” asked U.S. News & World Report.

One foreign service dispatch from the Embassy of New Delhi dated April 16, 1959 describes the many American expeditions involved in mountaineering and monster hunting in Nepal.

“American resources in the last two years have been concentrated on efforts to capture the abominable snowman,” the record reads.

Mark Murphy, in conversations with me, told of how he was well-aware of Tom Slick’s expeditions to Nepal, from his earlier reading of my book. He began to put two and two together when he found the documents. He immediately saw the link to what was being said and the Slick expeditions ground-breaking attempts to Nepal to find the Yeti.

Tom Slick, the Howard Hughes of cryptozoology, a Texas oil and beef millionaire, had sponsored, along with F. Kirk Johnson, another Texas millionaire, and the San Antonio Zoological Society, three separate expeditions to eastern Nepal to find the Yetis of the Himalayas and nearby region in 1957, 1958, and 1959.

During 1959, the United States government got interested probably because the Russians and Chinese took a heightened awareness of Slick’s treks to the region. While Slick was sincerely involved in the search for the Snowman, he also had intelligence connections of long-standing. Remember, it was the truly American thing to do back then, and although Slick was an advocate of world peace, he was also a patriot.

Slick’s expeditions found solid physical evidence (e.g. fecal material, hair samples, traditional art, footprints, bones) for the Yeti, but never the final ultimate proof, a body. Instead, Slick turned his support to the pursuit of Bigfoot in California and British Columbia in the Pacific Northwest.

Archivist Mark Murphy shows one of his favorite documents in the film clip, and does appear in and out of the entire four minutes. Murphy reads from the State Department cables containing regulations of the Government of Nepal for expeditions in search of the Yeti, also known as the Abominable Snowman.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Other Recent Cryptozoologists of the Year:

Cryptozoologist of 2010: Ngwe Lwin

Ngwe Lwin asking local people for information about a little-known new primate species he confirmed as a new discovery. Photo: FFI.

Cryptozoologist of 2009: Gabriele Gentile

Italian researcher Gabriele Gentile holds a Galápagos iguana, a newly-verified pink and black species he discovered in January 2009. Photo: Gabriele Gentile

Cryptozoologist of 2008: Andrea Marshall

In 2008, after over five years of on-site work and confirming lab findings, doctorate candidate Andrea Marshall identified the giant manta ray as a distinctive new species, separate from the reef manta ray. She may have also found evidence of a future new, third species of manta.

+++++++++

Thank you for your continued support of the International Cryptozoology Museum.

Thank you!

Follow CryptoZooNews

Not Found

The resource could not be found.