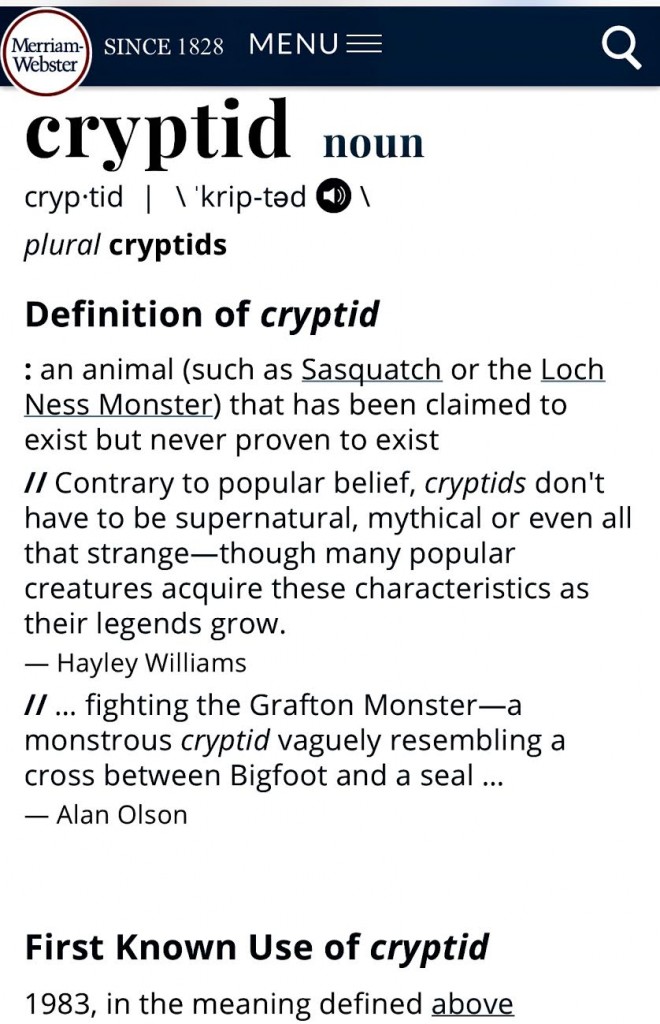

From the titles and content of adult nonfiction books to juvenile fiction, “cryptid” has been incorporated into our literature.

Thirty-six years after the term was coined, a foundation word in cryptozoology has reached a milestone.

On 4/22/2019, the Merriam-Webster editors added 640 new words to their latest dictionary, the company told CBS Chicago.

One of those new words is “cryptid,” which they announced by being a bit punny about it: “After years of searching for and collecting evidence, we put ‘cryptid’ in the dictionary.”

“Deciding what gets included is a painstaking process involving the Springfield, Massachusetts-based company’s roughly two dozen lexicographers, said Peter Sokolowski, Merriam-Webster’s editor at large. They scan online versions of newspapers, magazines, academic journals, books and even movie and television scripts until they detect what he calls ‘a critical mass’ of usage that warrants inclusion. The words are added to the online dictionary first, before some are later added to print updates of the company’s popular Collegiate Dictionary, which according to company spokeswoman Meghan Lunghi, has sold more than 50 million copies since 1898, making it the ‘best-selling hardcover book after the Bible.’” Source.

+++

Several people on social media have thanked me for “cryptid” being recognized as a new dictionary word. What is one to do when called a “living legend” so often? I am honored and humbled, because I have promoted “cryptozoology” and “cryptid” nonstop for decades. But realistically, John Wall and Richard Greenwell, who first coined the word and published it, respectively, must be remembered.

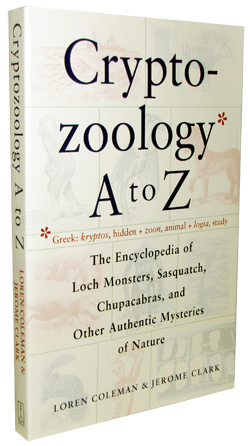

Most people are aware of “cryptid” first, of course, when it was discussed in Cryptozoology A to Z, in 1999. The text is still very popular as an e-book, hardback, and paperbound volume.

I can specifically point to who coined this word. In the Summer 1983 issue of the Newsletter (vol. 2, no. 2, page 10) of The International Society of Cryptozoology (the ISC is a now defunct organization), John E. Wall of Manitoba introduced the term he had invented for cryptozoological animals through a Letter to the Editor.

Cryptid denotes an animal of interest to cryptozoology, of course. Cryptids are in the most limited definition, either unknown species of animals or those that are thought to be extinct but which may have survived into modern times and await rediscovery by scientists.

From The Field Guide to Bigfoot and Other Mystery Primates

Writing in 1988 in Cryptozoology the journal of the then active ISC, Heuvelmans underscored the aims of cryptozoology:

“Hidden animals with which cryptozoology is concerned, are by definition very incompletely known. To gain more credence, they have to be documented as carefully and exhaustively as possible by a search through the most diverse fields of knowledge. Cryptozoological research thus requires not only a thorough grasp of most of the zoological sciences, including, of course physical anthropology, but also a certain training in such extraneous branches of knowledge as mythology, linguistics, archaeology and history. It will consequently be conducted more extensively in libraries, newspaper morgues, regional archives, museums, art galleries, laboratories, and zoological parks rather than in the field!”

![]()

For more information on one of Heuvelmans’ strangest investigations, see this book.

His definition of cryptozoology itself was exacting, for it gives his sense of what a cryptid is: “The Scientific study of hidden animals, i.e., of still unknown animal forms about which only testimonial and circumstantial evidence is available, or material evidence considered insufficient by some!”

Over the last few decades some have suggested that the science of cryptozoology should be expanded to include many animals as “cryptids,” specifically including the study of out-of-place animals, feral animals, and even animal ghosts and apparitions. Heuvelmans rejected such notions with typical thoroughness, and not a little wry humor:

“Admittedly, a definition need not conform necessarily to the exact etymology of a word. But it is always preferable when it really does so which I carefully endeavored to achieve when I coined the term `cryptozoology`. All the same being a very tolerant person, even in the strict realm of science, I have never prevented anybody from creating new disciplines of zoology quite distinct from cryptozoology. How could I, in any case?

“So, let people who are interested in founding a science of `unexpected animals`, feel free to do so, and if they have a smattering of Greek and are not repelled by jaw breakers they may call it`aprosbletozoology` or `apronoeozoology` or even`anelistozoology`. Let those who would rather be searching for `bizarre animals` create a `paradoozoology`, and those who prefer to go a hunting for `monstrous animals`, or just plain `monsters`, build up a `teratozoology` or more simply a `pelorology`.

“But for heavens sake, let cryptozoology be what it is, and what I meant it to be when I gave it its name over thirty years ago!”

Unfortunately, many of the creatures of most interest to cryptozoologists do not, in themselves, fall under the blanket heading of cryptozoology. Thus, many who are interested in such phenomena as the so-called Beasts of Bodmin and Exmoor (not unknown species but known species albeit in an alien environment) and the Devonshire/Cornwall “devil dogs” (not “animals” or even “animate” in the accepted sense of the word, and thus only of marginal interest to scientific cryptozoologists) think of these creatures as cryptids.

More broadly, then, we do not know whether a cryptid is an unknown species of animal, or a supposedly extinct animal, or a misidentification, or anything more than myth until evidence is gathered and accepted one way or another. Until that proof is found, the supposed animal carries the label cryptid, regardless of the potential outcome and regardless of various debates concerning its true identity. When it is precisely identified, it is no longer a cryptid, because it is no longer hidden.

While Heuvelmans created cryptozoology as a goal-oriented discipline (endeavoring to prove the existence of hidden animals), the fact that some of these cryptids will turn out not to be new species does not invalidate the process by which that conclusion is reached and does not retroactively discard the prior status as a cryptid. For example, the large unknown “Monster” in a local lake is a cryptid until it is caught and shown to be a known species such as an alligator. It is no longer hidden and no longer carries the label cryptid, but that does not mean it never was a cryptid.

An outsider is bound to be confused by a television program or magazine article that highlights reliable eyewitnesses and physical evidence for hairy bipeds or Lake and Sea Monsters, then jumps to a story about phantom dogs or glowing swamp creature. That confusion is understandable. It is often impossible to tell which category an unknown animal actually inhabits until you catch it. Until then, it is a cryptid.

+++

For more information on “cryptids,” please plan to attend

The Fourth Annual International Cryptozoology Conference

Portland, Maine

April 26-28, 2019

Click on link for more information.

Follow CryptoZooNews

Not Found

The resource could not be found.