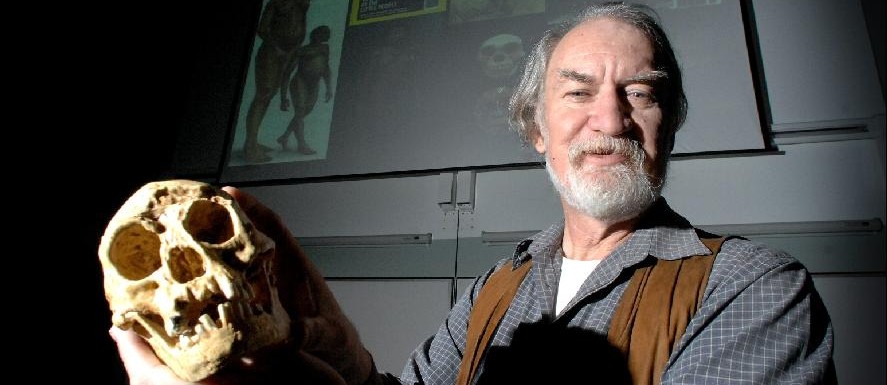

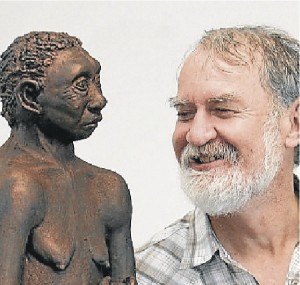

A colleague has died. A personal correspondent of mine for almost a decade, and a friend to cryptozoology, the 62-year-old Australian archaeologist who startled the world of anthropology with his discovery of a tiny new species of human known as the “hobbit” has died. He passed away after a year-long battle with aggressive prostate cancer, his university said Wednesday, July 24.

Mike Morwood, the professor who was instrumental in the discovery of Homo floresiensis in 2003, died on Tuesday, 23 July 2013, the University of Wollongong said.

New Zealand-born Morwood earned his PhD from the Australian National University in Canberra, and became an expert on Aboriginal rock art, having carried out extensive research in Queensland and Western Australia states early in his career.

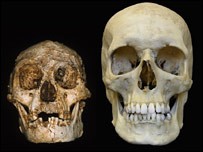

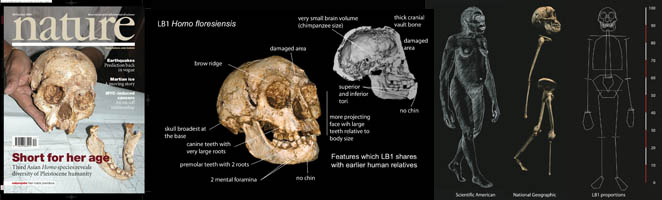

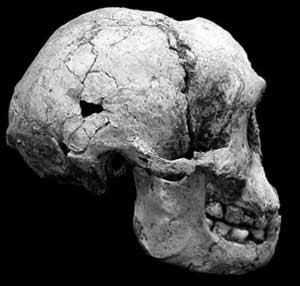

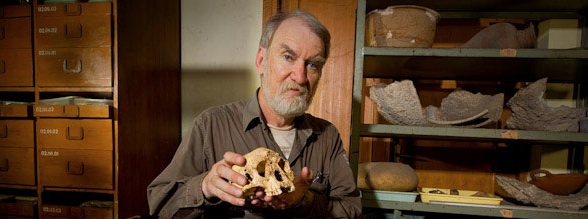

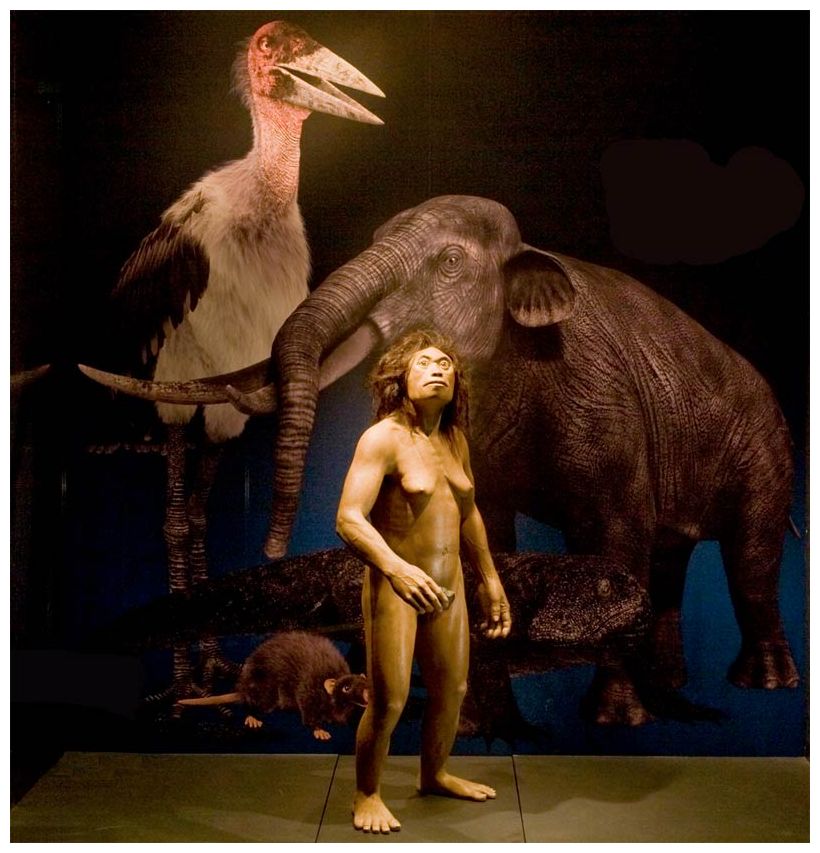

He is best known for leading the team of Australian and Indonesian researchers that uncovered the partial skeleton of a one meter tall (3.25 foot) woman at Liang Bua, a limestone cave on the Indonesian island of Flores in 2003. He continued to find, and established that a population of Homo floresiensis had lived at the site for thousands of years.

The find shook the world of paleoanthropology because it showed that humans concurrently were living with little people. The facts were hard to ignore. The discovery also impacted cryptozoology.

Henry Gee, the editor of Nature, in an editorial entitled “Flores, God and Cryptozoology,” forever tied the finding of the “Hobbits” to cryptozoology. He wrote: “The discovery that Homo floresiensis survived until so very recently, in geological terms, makes it more likely that stories of other mythical, human-like creatures such as Yetis are founded on grains of truth….Now, cryptozoology, the study of such fabulous creatures, can come in from the cold.”

In March 2005, an independent team of international scientists backed Morwood’s and the other Australian scientists’ 2004 claim that the bones of Homo floresiensis found on the island of Flores was a valid new species. The Australian scientists’ skeptics had said the bones are only those of a diseased human, similar to how the first Neanderthal was dismissed as an old, diseased Cossack soldier.

Also in 2005, the original discoverers were more open to discussing their initial sense that Homo floresiensis might actually be closer to Australopithecus than Homo. Speculation as to the linkages of Homo floresiensis to Australopithecus was there from the first. Mike Morwood, Peter Brown, and others on the original team had that thought from the start, and it remained as part of their ongoing considered analysis of the finds.

Looking back to 1955, in the writings of cryptozoologist Bernard Heuvelmans, he bravely (for his time) wondered aloud if reports of small hominids in Africa were australopithecines. There is even a scientific article in 1945, by London University’s Professor W. C. Osman-Hill, which speculated that historically remembered “little people” in south Asia might one day be found to have been based on relict diminutive representatives of Homo erectus.

This was long before we knew about Homo floresiensis or the contemporary tales of Ebu Gogo. Osman-Hill studied similar folklore, for example, of the Nittaewo, the three feet tall hairy hominids of ancient Ceylon (Sri Lanka). The Nittaewo were mentioned by Pliny in the first century. They were said by Osman-Hill to have existed, at least, to the end of the 18th Century before being exterminated by “modern” humans through methods that mirror how the humans of Flores talk about killing off the Ebu Gogo (via fires at the entrances of caves).

The initial Morwood find was reinforced in context by the mounting evidence of other skeletal remains for other individuals like the original three-feet tall Flores discovery, LB1, of Homo floresiensis. This skeletal material was described and discussed from at least ten other Homo floresiensis, putting to rest that the first discovery was merely of an individual anomaly.

In October 2005, in Nature, Mike Morwood’s team described more fossil remains, including a mandible, arm and other similarly small bones from nine individuals. Two mandibles also share dental features and lack of a chin, a portion of the jaw common to all Homo sapiens regardless of size.

“We can now reconstruct the body proportions of H. floresiensis with some certainty,” the researchers wrote in the October 11, 2005, online issue of the journal Nature. “The finds further demonstrate the LB1 … is not just an aberrant or pathological individual but is representative of a long-term population.”

Soon after the discovery of Homo floresiensis, Michael Morwood would tell New Scientist: “Although we only have one cranium, the other bones we found show that LB1 was a normal member of an endemically dwarfed hominid population.”

The distinctive traits of reduced body mass, reduced brain size and short thick legs mirror those found in other island endemic populations of large mammals, Morwood said at the time. He called the microcephaly explanation “bizarre.” It ignores other evidence from Liang Bua and the literature on island endemic evolution, he says.

Talking to the Sydney Morning Herald, Mike Morwood, co-leader of the Australian and Indonesian team that discovered the remains, dismissed Martin’s claims published in the journal Science as bizarre and unsubstantiated. “I’m surprised Science published their study,” said Morwood.

Morwood did not slow down in his efforts to expand his finds. He wrote on his own university page, the following, in recent months, about Homo floresiensis and beyond:

This species had a range of very primitive traits, but existed on Flores until a mere 17,000 years ago. It has prompted reassessment of fundamental tenets in palaeoanthropology – for instance, concerning the peripheral role of Asia in early hominin evolution, the nature of genus Homo; and the relationships between brain size and intelligence. As a result, there has been intense public interest in LB1 – as evident in popular books, refereed journals, magazines, radio and television programs, documentary films, internet websites, museum displays and public lectures.

More recently, the faunal sequence and minimum age for hominins on Flores has been pushed back to 1.1 million years ago. This has opened up a Pandora’s Box of possibilities – for instance, that pre-modern hominins colonised other islands in the region, where many endemic species may have evolved. Some of these possibilities are now being followed up in a new project ‘In search of the first Asian Hominins: Excavations at Mata Menge, Flores, Indonesia’.

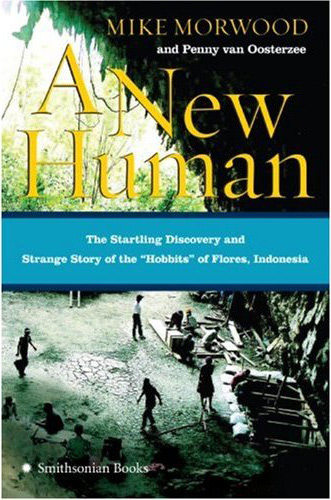

Morwood would go on to write other scientific papers on the discovery, as well as the book, A New Human: The Startling Discovery and Strange Story of the “Hobbits” of Flores, Indonesia by Mike Morwood and Penny Van Oosterzee.

“He was inevitably a game-changer, who made an extraordinary contribution to their field,” University of Western Australia academic Alistair Paterson told the Agence France-Presse on Wednesday.

Mike Morwood was a grand and good person, and he will be missed beyond the worlds of anthropology, archaeology and cryptozoology. He was a passionate man who lived a passionate life.

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Jen King captured some of these personal moments in these details:

Michael John Morwood was born in Auckland, New Zealand on 27 October 1950 to William, a baker, and Dulcie Morwood.

He was educated at the University of Auckland before migrating to Australian in 1974. He continued his studies and completed a PhD on the rock art and archaeology of Queensland at the Australian National University (ANU) in 1980.

Professor Morwood initially researched archaeology in the Cape York Peninsula, south-east Queensland, central Queensland and the Kimberley regions and became a world authority on Aboriginal rock art and his findings contributed greatly to our understanding of Australia’s ancient history.

This work emphasised the importance of a landscape approach and holistic context in archaeological explanation.

The work he undertook in the Kimberley initiated a study of Asian trepang sites on the coast of Australia. Trepang, or sea cucumbers, were prized for their medicinal and culinary attributes and were harvested by Makassan trepangers from Sulawesi from about 1720.

Professor Morwood’s research of these sites reflected the nature of relations between Indigenous Australian and Asian communities.

Prior to his death, he was involved in a collaborative project with colleagues at the University of New England and Macquarie University researching a theory of the Kimberley region as the likely beachhead for the initial habitation of Australia.

When not digging in Indonesia or exploring Aboriginal cave art, Professor Morwood was a proponent of the Japanese martial art of Aikido which he practiced for many years.

He was also a collector of swords from Japan, China, the United States and the Makasar region.

Professor Morwood is survived by his wife, Francelina, his former wife, Kathryn, a daughter and two grandchildren.

Personally, I feel very touched by Mike Morwood’s death. He kindly exchanged emails and materials with me, without bias, to someone who was intrigued by the possible cryptozoologically implications of his discovery. A friend has joined the timeline of humankind and, while he was among us, enriched our understanding of humanity. He will be missed.

MIKE MORWOOD/Selected Publications

BOOKS

Aziz, F., Morwood, M.J. & van den Bergh, G.D. (eds) 2009. Pleistocene geology, palaeontology and archaeology of the Soa Basin, central Flores, Indonesia. Indonesian Geological Survey Institute, Bandung. 146 pages ISSN 0852-873X.

Morwood, M.J. 2002. Visions from the past: the archaeology of Australian Aboriginal art. Allen and Unwin, Sydney; 347 pages.

Morwood, M.J. and van Oosterzee, P. 2007. The discovery of the Hobbit: the scientific breakthrough that changed the face of human history. Random House, Sydney; 326 pages.

Morwood, M.J. & Jungers, W.L. (Guest editors) 2009. Paleoanthropological Research at Liang Bua, Flores, Indonesia. Journal of Human Evolution (Special Issue) 57(5) November 2009.

JOURNALS

Morwood, M.J. & Hobbs, D.R. (1997). The Asian connection: preliminary report on Indonesian trepang sites on the Kimberley coast, N.W. Australia. Archaeology in Oceania 32, 197-206.

Brown, P., Sutikna, T., Morwood, M.J., Soejono, R.P., Jatmiko, Saptomo, E.W. & Rokus, A.D. (2004). A new small bodied hominin from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia. Nature 431, 1055-1061.

Morwood, M.J., Soejono, R.P., Roberts, R.G., Sutikna, T., Turney, C.S.M., Westaway, K.E., Rink, W.J., Zhao, J-x., van den Bergh, G.D., Rokus, A D., Hobbs, D.R., Moore, M.W., Bird, M.I. & Fifield, L.K. (2004). Archaeology and age of Homo floresiensis, a new hominin from Flores in eastern Indonesia. Nature 431, 1087-1091.

Morwood, M.J., Brown, P., Sutikna, T., Jatmiko, Saptomo, E.W., Westaway, K.E., Roberts, R.G., Rokus, A.D., Maeda, T , Wasisto, S. & Djubiantono, T. (2005). Further evidence for small-bodied hominins from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia. Nature 437, 1012-1017.

Westaway, K.E., Morwood, M.J., Roberts, R., Rokus, A.D., Zhao, J.-x., Storm, P., Aziz, F., van den Bergh, G.D., Hadi, P., Jatmiko, & de Vos, J. (2007). Age and biostratigraphic significance of the Punung Rainforest Fauna, East Java, Indonesia, and implications for Pongo and Homo. Journal of Human Evolution 53, 709-717.

Jungers, W.L., Larson, S.G., Harcourt-Smith, W., Morwood, M.J. & Sutikna, T. (2009). Description of the lower limb skeleton of Homo floresiensis. Journal of Human Evolution 57, 538-554.

Larson, S.G., Jungers, W. L., Harcourt-Smith, W., Morwood, M J. & Sutikna, T. (2009). Description of the upper limb skeleton of Homo floresiensis. Journal of Human Evolution 57, 555-570.

Morwood, M.J. et. al. (2008). Climate, people and faunal succession on Java, Indonesia: evidence from Song Gupuh. Journal of Archaeological Science 35, 1776-89.

Falk, D., Hildebolt, C., Smith, K., Morwood, M.J. , Sutikna, T. , Jatmiko, Saptomo, E.W. & Prior, F. (2009). LB1’s virtual endocast, microcephaly, and hominin brain evolution. Journal of Human Evolution 57, 597-607.

Hochnell, S.A., Piper, P.J., van den Bergh, G D , Rokus A.D., Morwood, M.J. & Kurniawan, I. (2009). Dragon’s Paradise Lost: palaeobiogeography, evolution and extinction of the largest-ever terrestrial lizards (Varanidae). PLoS ONE 4(9): e7241. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007242 (Zoological Society of London, UK).

Moore, M.W., Sutikna, T., Morwood, M.J. & Brumm, A. (2009). Continuities in Stone Flaking Technology, Liang Bua, Flores, Indonesia. Journal of Human Evolution 57, 503-526.

Morwood, M.J. & Jungers, W.L. (2009). Conclusions: implications of the Liang Bua finds for hominin evolution and biogeography. Journal of Human Evolution 57, 640-650.

Morwood, M.J., Sutikna, T., Saptomo, E.W., Jatmiko, Hobbs, D.R. & Westaway, K.E. (2009). Preface: research at Liang Bua, Flores, Indonesia. Journal of Human Evolution 57, 437-449.

Westaway, K.E., Roberts, R.G., Sutikna, T., Morwood, M.J, Zhao, J.-x, Chivas, A.R. & Gagan, M.K. (2009). The evolving landscape and climate of western Flores: an environmental context for the archaeological site of Liang Bua. Journal of Human Evolution 57, 450-464.

Westaway, K.E., Sutikna, T., Saptomo, W.E, Jatmiko, Morwood, M.J., Roberts, R.G. & Hobbs, D.R. (2009). Reconstructing the geomorphic history of Liang Bua: a stratigraphic interpretation of the occupational environment. Journal of Human Evolution 57, 465-483.

Brumm, A., Jensen, G., van den Bergh, G.D., Morwood, M.J., Kurniawan, I., Aziz, F. & Storey, M. (2010). Hominins on Flores, Indonesia, by one million years ago. Nature 464, 748-752.

Morwood, M.J., Walsh, G.L. & Watchman, A. (2010). AMS radiocarbon ages for beeswax and charcoal pigments in north Kimberley rock art. Rock Art Research 27, 3-8.

Footnote: Flores has continued to reveal many surprises, including giant storks.

Follow CryptoZooNews

Not Found

The resource could not be found.