Sterling Edmund Lanier, 79, who just died in Sarasota, Florida, harkens back to an era of early cryptozoologists and adventurers.

Lanier worked as an editor at Chilton Books in the 1960s, alongside Ivan T. Sanderson, also an editor at Chilton. Chilton Books in 1961 published Sanderson’s famous book, Abominable Snowmen: Legend Come to Life. Sanderson and Lanier moved in similar natural history and publishing circles for a few years. Lanier wrote the foreword for one of Sanderson’s friends, Roger A. Caras’ 1964 Chilton-published book, Dangerous to Man; Wild Animals A Definitive Study of Their Reputed Dangers to Man.

Born in 1927 in New York City, Sterling E. Lanier started early to be a lifelong fan of fantastic fiction. He devoured the Sherlock Holmes stories at age 14, and was a penpal of The Lord of the Rings creator J.R.R. Tolkien. Lanier trained as an anthropologist-archaeologist and worked for a brief period as a research historian.

In 1961, Lanier began at Chilton editing books, and, as is widely noted, Lanier’s most discussed achievement as an editor was the commissioning of Frank Herbert’s popular seminal science fiction work Dune, which had been rejected by many other publishers.

Lanier turned freelance in 1967, as both a sculptor (in bronze, silver and gold) and an author. His sculptures have been exhibited by many museums, including the Smithsonian. They also turn up in his significant footnote in cryptozoological coelacanth lore.

Within cryptozoology, one tale about the possible survival of coelacanths in the Western Hemisphere involves Lanier. Michel Raynal’s “An Unknown Species of Coelacanth in the Gulf of Mexico?”, about accounts of silver coelacanths and Mexican murals of possible coelacanths, also discusses anomalous large, shiny scales that some have linked to a possible new population of coelacanths.

One report of unidentified scales, Raynal mentions, has been recorded in 1993 by J. Richard Greenwell, secretary of the now-defunct International Society of Cryptozoology. “American naturalist Sterling Lanier,” as he was identified, told Greenwell this story:

About 20 years before [ca. 1973], when he was selling his well-known brass figurines of fossil animals at an outdoor art show near Florida’s Gulf coast, another artist was displaying a necklace made of fish scales that “looked very much like those of Latimeria.”

He [Lanier] had extracted them from a pile of “trash” fish, crabs, and seaweed from a Gulf shrimp boat. “He had caught their glitter,” recalls Lanier in his statement, “and picked them out, one by one.”

The owner let Lanier examine and sketch the scales, but he refused to sell the necklace. Unfortunately, Lanier, now retired in Sarasota, Florida, has lost the original notes and sketches, and all we have is his statement. – Richard Greenwell 1994.

When Lanier retired from the hustle bustle of New York, he had moved to Sarasota, Florida with his wife, Ann.

Sterling E. Lanier’s many stories featured prominently in the contemporary leading science fiction and fantasy publications. Many of them had various cryptofiction elements, long before “cryptofiction” was even a term being used.

One of Lanier’s most famous characters, the exotic Brigadier Ffellowes might actually be called a crypto-adventurer. Lanier’s major achievement in fantasy fiction writing was the sequence of thirteen stories chronicling the fabulous adventures of Brigadier Ffellowes, a character suggested by Conan Doyle’s Napoleonic tales of Brigadier Gerard and undoubtedly inspired by Lanier’s own upbringing within a military family (indeed, the first collection of Ffellowes stories is dedicated to his father, a United States Navy captain).

These stories include, as noted by reviewer Anne B. Rider, retired Brigadier Ffellowes at a gentlemen’s club recounting mysterious tales from his travels abroad, which include the keeper of the sea serpents, the half-human survivors of ancient At’lantz, the strange cries heard on an island of turtles, the real meaning of the Loch Ness Monster, and how Ffellowes’ father worked with (and was rejected by) an imperious London detective hunting the Giant Rat of Sumatra.

If there’s any doubt that Lanier did not target cryptids in some of his works, merely examine his 1989 anthology, Seaserpents!.

Sterling Lanier’s authored works include:

Collections:

* The Peculiar Exploits of Brigadier Ffellowes (1971)

* The Curious Quests of Brigadier Ffellowes (1986)

Anthologies:

* Sorcerers! (1986)

* Atlantis (1988)

* Seaserpents! (1989)

* Horses! (1994)

* The Oxford Book of Fantasy Stories (1994)

Novels:

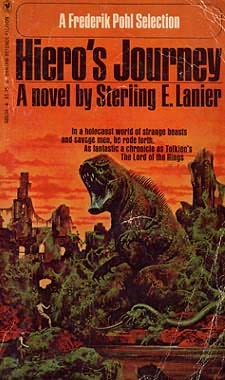

* Hiero’s Journey (1975)

* The Unforsaken Hiero (1983)

Short Stories:

* His Coat So Gay (1970)

Series:

* Hiero’s Journey

* Magic Tales!

* Brigadier Ffellowes

* Oxford Books of Prose

* Isaac Asimov’s Magical Worlds of Fantasy

The following is the non-cryptozoological mention of Sterling E. Lanier’s passing that alerted me to his death. I decided to give the cz background (above) that was not revealed in this initial notice:

Locus (an online site for News, Reviews, Resources, and Perspectives of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror) has received a report of the death of writer and editor Sterling E. Lanier, born 1927, on June 28, 2007, in Sarasota, Florida, at the age of 79.

Lanier began publishing in 1961, and was best known for stories about Brigadier Ffellowes and the novel Hiero’s Journey (1973). As editor he worked for Chilton Books in the early 1960s, where he persuaded the firm to publish Frank Herbert’s Dune (1965). Lanier’s last novel was Menace Under Marswood (1983). He was also a sculptor whose works included visions of characters from The Lord of the Rings that were admired by J.R.R. Tolkien himself.Thomas B. Allen

Follow CryptoZooNews

Not Found

The resource could not be found.