John Bindernagel, 76, passed away during the evening of January 17, 2018.

John was a great friend to many in the field. I remember talking birds with him when we were together at Craig Woolheater’s conference in Texas, of Bigfoot at Beachfoot in Oregon, and about Sasquatch when at John Green’s tribute in British Columbia. His legacy will be profound.

Texas Bigfoot Conference 2002

John Bindernagel, Bobby Hamilton, Loren Coleman, Chester Moore

Photo: Craig Woolheater

On January 8, 2018, Bindernagel informed his “circle of friends…of just how imminent” his death may be. “After two years of cancer chemotherapy and a year of radiation treatment,…my own terminal cancer is now restricted to pain management.”

For the last few days, Bigfoot community individuals have been sending messages to online forums and lists telling of their great respect for this gentle man.

John in 2018

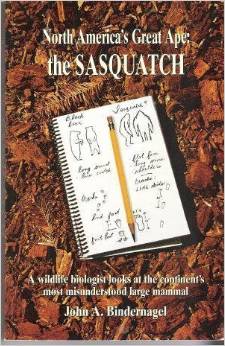

John A. Bindernagel was a wildlife biologist, since 1963. He published a book in 1998 entitled North America’s Great Ape: the Sasquatch, and later in 2010, The Discovery of Bigfoot.

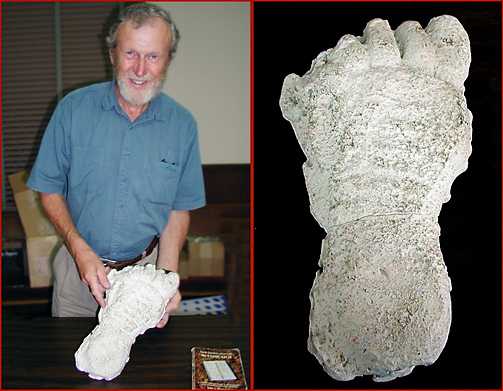

Bindernagel born in 1941, grew up in Ontario, attended the University of Guelph and received a PhD in Biology from the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He moved to British Columbia in 1975, largely because the region was a hot spot for Bigfoot sightings. Over the years, he collected casts of tracks that he felt belonged to Bigfoot. He also claimed to have heard the creature near Comox Lake in 1992, comparing its whooping sound to that of a chimpanzee. Bindernagel considered that the Bigfoot phenomena should receive more attention from serious scientists, but once remarked, “The evidence doesn’t get scrutinized objectively. We can’t bring the evidence to our colleagues because it’s perceived as tabloid.”

He penned the following about himself:

I am a professional wildlife biologist who is seriously studying the sasquatch or bigfoot in North America. My interest in this animal began in 1963 when, as a third-year-student in wildlife management at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, I was laughed at for raising the report of an animal described as an “ape-man” for possible discussion. My field work began in 1975 when our family moved to British Columbia, partly in order for me to begin field work on this species. In 1988, my wife and I found several sasquatch tracks in good condition in the mountains not far from our home on Vancouver Island. Plaster casts which we made from these tracks provided the first physical evidence for the existence of the sasquatch. Wildlife biologists such as myself regularly depend on tracks and other wildlife sign as evidence for the presence of bears, deer, wolves, and other mammals, recognizing that tracks constitute a more reliable and persistent record of the presence of a mammal species in an area than a fleeting glimpse of the animal itself. I am satisfied that the sasquatch is an extant (or “real”) animal, subject to study and examination like any other large mammal, and am much more concerned with addressing ecological questions such as how it overwinters in the colder regions of North America, than with dwelling on the controversy of whether it does or does not exist. I remain aware, however, that many people—including scientific colleagues—remain unaware of the information that exists about this species.

Before his death, Bindernagel registered the following complaint against the casual shortening of the term, Sasquatch:

I would be remiss if I did not register my disappointment at the recent and increasingly widespread use of the terms “squatch,” and “squatching,” which denigrates the Halcolmelm (Coast Salish) name Sasq‘ets, anglicized many years ago as “sasquatch,” and which has been more-or-less accepted by the relevant Aboriginal people.

Along with many of my Aboriginal friends, co-workers, and colleagues—and more than a few non-native investigators—I am saddened and disappointed by the lack of sensitivity displayed by the increasing use of the term “squatch” to describe a being of cultural importance to North American Aboriginal people. As if, by so doing so, we have appropriated it as our own.

It is similar disappointing to hear dedicated research into this subject by both serious amateurs and professional investigators denigrated as a trivial or recreational activity, increasingly referred to as “squatching.”

I understand that many people using these terms are unaware of the cultural importance—even sacredness—of the sasquatch to many Aboriginal people, and have no ill intent. They may acknowledge, as I do, that as non-native investigators, we are mere upstarts, adding only a little to the centuries-old knowledge that Aboriginal people have acquired regarding this mammal. Consequently, I suggest that we make greater efforts to respect Aboriginal knowledge, even if it is embodied in myth and legend beyond our easy understanding. The fact that Aboriginal sasquatch knowledge has been misunderstood, even by cultural anthropologists, as fictional, does not excuse a careless or disrespectful approach to someone else’s language on our part.

I have addressed the “easy” interpretation of sasquatch as myth (in the narrow sense of fictional in chapter 15 of The Discovery of the Sasquatch: Reconciling Culture, History, and Science in the Discovery Process of the Sasquatch: Sasquatch as Myth (in Part 5: Reconsidering Prevailing Knowledge)

I pointed out how cultural anthropologists have, in the past, similarly denigrated Aboriginal reports of sasquatches, when they dismissed them as supernatural beings.

When the discovery of the sasquatch as an extant North American mammal is finally acknowledged, we will owe a huge debt to Aboriginal people for their willingness to explain the sasquatch to disbelieving anthropologists. We must affirm and applaud their efforts to educate us, to bring us onside, so to speak, just as we investigators seek the attention of relevant scientists within the scientific community to scrutinize the evidence we present for their considered (but still withheld) attention. ~ May 16, 2014.

Bindernagel’s heart was always in the right place.

(Unknown to Bindernagel, perhaps, is that the use of “Squatch” predates Bobo and Finding Bigfoot. As Wikipedia points out, “Squatch (a derivation of Sasquatch) was the team mascot for the Seattle SuperSonics of the National Basketball Association. Between his 1993 debut and the team’s relocation in 2008 to Oklahoma City, Squatch appeared at more than 175 events annually, and was with the organization during their run to the 1996 NBA Finals.”)

The cast of the footprint personally found by John Bindernagel.

The information about the author John approved for his books.

John Bindernagel will be remembered as one of the best of the best.

He will be missed.

Condolences to his family, friends, and colleagues.

Sad day. He will be missed.

Good day, Im contacting you to learn if Dr Bindernagels research will be carried on by another. I am a rookie field researcher and have no confidence in any of the organizations which claim to be valid scientific evidence gatherers with the exception of Dr Jeffrey Meldrum. But frankly I greatly preffered Dr Bindernagels demeanor and outlook on the subject. If you would be so kind as to reply I can be contacted at Grizzly3208@hotmail.com . Any coorespondence will be held strictly confidential and Im truly sympathetic to your loss. May he walk in the spirit of the Guardian of the forest and with our lord Jesus. Thank You. Sincerely Dean Kestner of Penna.

[...] Wildlife Biologist and Sasquatch Researcher John Bindernagel Dies [...]