Canadian John Bindernagel (born 1941), has a doctorate in biology and is the author of North America’s Great Ape: The Sasquatch (1998) and The Discovery of Sasquatch (2010).

John is a man I have grown to known over the years, through conferences and correspondence, a quiet birder, and steady Bigfoot researcher. And yet John has shown a new side, of late. A side that may surprise some folks.

Bindernagel has registered the following complaint against the casual shortening of the term, Sasquatch:

I would be remiss if I did not register my disappointment at the recent and increasingly widespread use of the terms “squatch,” and “squatching,” which denigrates the Halcolmelm (Coast Salish) name Sasq‘ets, anglicized many years ago as “sasquatch,” and which has been more-or-less accepted by the relevant Aboriginal people.

Along with many of my Aboriginal friends, co-workers, and colleagues—and more than a few non-native investigators—I am saddened and disappointed by the lack of sensitivity displayed by the increasing use of the term “squatch” to describe a being of cultural importance to North American Aboriginal people. As if, by so doing so, we have appropriated it as our own.

It is similar disappointing to hear dedicated research into this subject by both serious amateurs and professional investigators denigrated as a trivial or recreational activity, increasingly referred to as “squatching.”

I understand that many people using these terms are unaware of the cultural importance—even sacredness—of the sasquatch to many Aboriginal people, and have no ill intent. They may acknowledge, as I do, that as non-native investigators, we are mere upstarts, adding only a little to the centuries-old knowledge that Aboriginal people have acquired regarding this mammal. Consequently, I suggest that we make greater efforts to respect Aboriginal knowledge, even if it is embodied in myth and legend beyond our easy understanding. The fact that Aboriginal sasquatch knowledge has been misunderstood, even by cultural anthropologists, as fictional, does not excuse a careless or disrespectful approach to someone else’s language on our part.

I have addressed the “easy” interpretation of sasquatch as myth (in the narrow sense of fictional in chapter 15 of The Discovery of the Sasquatch: Reconciling Culture, History, and Science in the Discovery Process of the Sasquatch: Sasquatch as Myth (in Part 5: Reconsidering Prevailing Knowledge)

I pointed out how cultural anthropologists have, in the past, similarly denigrated Aboriginal reports of sasquatches, when they dismissed them as supernatural beings.

When the discovery of the sasquatch as an extant North American mammal is finally acknowledged, we will owe a huge debt to Aboriginal people for their willingness to explain the sasquatch to disbelieving anthropologists. We must affirm and applaud their efforts to educate us, to bring us onside, so to speak, just as we investigators seek the attention of relevant scientists within the scientific community to scrutinize the evidence we present for their considered (but still withheld) attention. ~ May 16, 2014.

The rapid enculturation of the words “Squatch” and “Squatching” in North American society appears to be directly related to the popularity of the Animal Planet series, Finding Bigfoot (2011-present). The increased use of these phrases occurred in the wake of James “Bobo” Fay, one of the four regular Bigfooters on Finding Bigfoot, employing forms of “Squatch.” Fay is well-known for his “Gone Squatchin’” baseball-style cap.

Unknown to Bindernagel, perhaps, is that the use of “Squatch” predates Bobo and Finding Bigfoot.

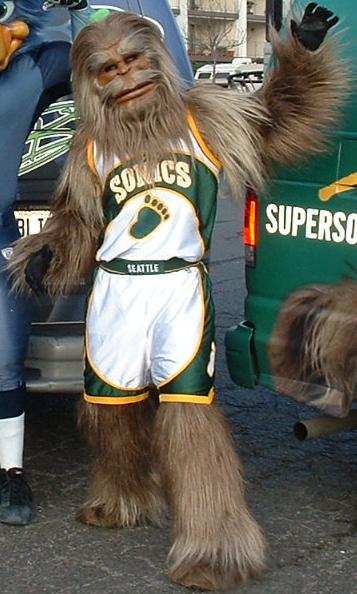

Squatch in 2005.

As Wikipedia points out, “Squatch (a derivation of Sasquatch) was the team mascot for the Seattle SuperSonics of the National Basketball Association. Between his 1993 debut and the team’s relocation in 2008 to Oklahoma City, Squatch appeared at more than 175 events annually, and was with the organization during their run to the 1996 NBA Finals.”

Follow CryptoZooNews

Not Found

The resource could not be found.