Yeti and Bigfoot Seeker Peter Byrne Dies

by Loren Coleman, Director, International Cryptozoology Museum

The Abominable Snowmen and Bigfoot hunter, Peter C. Byrne has died, at the age of 97, on Friday, according to one report, at around noon, but more specifically, at 4:44 PDT, on July 28, 2023. He lived a long and dedicated life, in pursuit of cryptozoological subjects, and achieved what few could imagine, routinely finding sponsorships for his searching for Yeti and North American Sasquatch, for almost six decades. At the end of his life, in the early 2000s, Byrne retired to a modest home on a salmon-filled river near Pacific City, Oregon, after some rocky years of controversial moments that will not distract from his legacy.

Herewith is a final tribute and detailed remembrance of the well-known explorer.

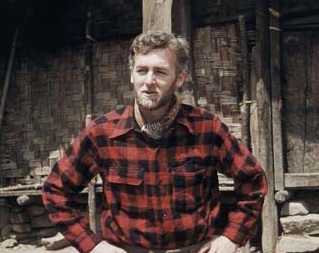

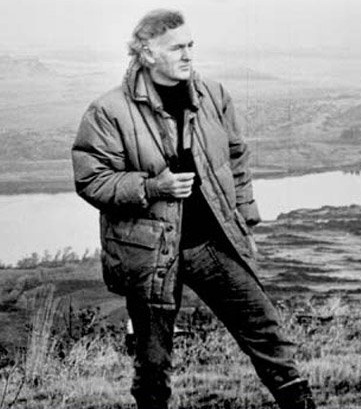

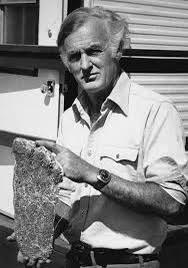

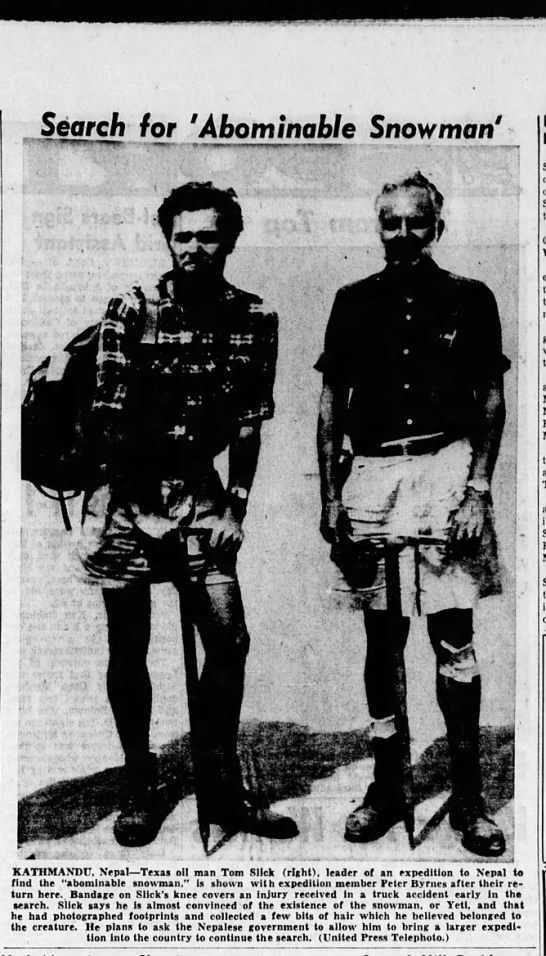

Peter Byrne in Nepal, 1958, during his Tom Slick-sponsored quest for the Yeti in the late 1950s.

Early Days of Peter Byrne

Peter Cyril Byrne was born in Dublin, Ireland, on August 22, 1925, to an Irish father and an English mother. His father owned a generous 300 acre Irish farm where Peter grew up, hunting and fishing. He graduated from school, and in 1943, Byrne went on to serve in World War II. He enlisted in the Royal Air Force and was stationed on an island in the Indian Ocean piloting rescue boats originally designed after WWI by Thomas Edward Lawrence, “Lawrence of Arabia” (1888-1935). In the south Asia war theater, Byrne was promoted to Leading Aircraftman, earning personal honors and three campaign metals.

Enter Tom Slick

After his service, Byrne came to work on a tea plantation in northern India in the late 1940s; he opened Nepal’s first tiger hunting concession (at the end of his life, he helped protect them) and soon found himself face to face with stories about the Abominable Snowman or Yeti. In 1956, after a couple of years without a vacation, from a job which many people would consider a working vacation, Byrne requested leave from the tea plantation for a trek to Zongri, Sikkim, an Indian state on the east boundary of Nepal. There he learned much about the Yeti and determined to search for the mysterious creature, which was said to descend in winter to villages and howl in the night.

1956 proved a very productive year for Peter. Again, with an official permit, he trekked deep into Sikkim where he met Tenzing Norgay, who in 1953, crested Mt. Everest with Sir Edmund Hillary. They became friends. Once while they were talking, Tenzing told Peter something that would shape his life for decades. Amazingly, and fortuitously, earlier that summer Tenzing had met another American who was wandering in search of the Yeti. Tenzing said the man left a note with his wife and that Peter was welcome to see it.

Back in Tenzing’s Darjeeling home, Peter visited Mrs. Norgay. “Of course,” she remembered the very nice American who wanted to know about the Yeti, and buy some of their Lhasa Apso puppies. She produced “a scrap” of paper with this note: “Thom Slick, c/o The National Bank of Commerce, San Antonio, Texas.”

Then in 1957, Tom Slick agreed to Peter Byrne’s proposal for a Yeti expedition and arrived in Nepal for a one month reconnaissance with Peter. It began on St. Patrick’s Day, as did other of Slick’s treks.

After a month of hiking about, including a bus-related knee accident, Slick (and especially his mother) had enough of Nepal, and Slick returned to the oil fields in Oklahoma and Texas. Nevertheless, Slick funded Byrne’s long expeditions in 1958 and 1959 for the search for the Yeti. Slick requested detailed reports on work effort and dollars spent. Those years unhappily resulted in no photographs or body of a Yeti.

By the end of the 1950s, Byrne’s three-year mission to hunt and track down the Yeti came to an end.

I documented these expeditions by Tom Slick, and Peter Byrne’s involvement in them in two books published in 1989 and 2002.

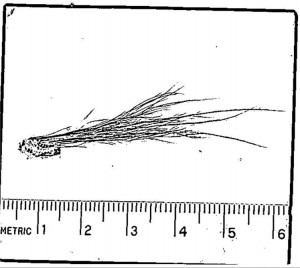

The Slick-Johnson expeditions, which Byrne was a member, found footprints and a mummified hand in a monastery. Byrne took the Pangboche finger and replaced it with a human finger; the finger was tested and found to be somewhere between human, gorilla and chimpanzee, but the finger was supposedly lost. The creature remained shrouded in the blowing Himalayan snow.

Then the hunt shifted from Nepal to the Pacific Northwest.

The Texas oil and beef millionaire Tom Slick liked to be in control of everything. In California, and soon in British Columbia, while Slick was the “leader” and Titmus was the “field leader” or “deputy leader,” the pull of Slick’s other obligations distracted him from the hunt. Slick needed someone he knew to be in charge, and that someone was Peter Byrne, who had been his point man in the Yeti hunt.

Byrne, Irish-born, refined, a dashing and successful big game hunter of tiger and elephant in India and Nepal, had found his first Yeti print in 1948 in Sikkim. He had first met Tom Slick in a valley in the Himalayas in 1956, and had grown to know Slick through their shared love of adventure, women, and a similar lifestyle. He had headed Slick’s rather successful searches for Yeti in 1957, 1958, and 1959, which had discovered tracks in snow and mud, and the mysterious Pangboche Yeti hand.Hearing of the discovery of big footprints in northern California, Slick asked Byrne to head up a “Pacific Northwest Bigfoot Expedition.”

So, on Christmas 1959 Slick sent a message to end the search for the Yeti. But Slick’s enthusiasm for the search didn’t wane; he wanted Peter to come to the Pacific Northwest to search for Bigfoot. In 1960, the quest, for a short time, included the Byrnes, Rene Dahinden, John Green and Bob Titmus.

So Slick flew his friend, Peter Byrne, and Peter’s brother, Bryan, over from Nepal, and early in 1960, Byrne had become the new leader of The Pacific Northwest Expedition.

The Byrnes did their best to organize the effort, but money, equipment, and men had been lost. Before they returned to Canada, Titmus, Green, and Dahinden shared duties in the Pacific Northwest Expedition with the Byrnes. Everyone has their own view of those days, and it is obvious that no one got along with one another—or Peter Byrne. Dahinden called the expedition a “total screw up,” but Dahinden was not an easy person to be around either.

“René had a nasty habit of pacing in front of the campfire and spitting into it,” John Green recalled for Vancouver Courier reporter Robin Brunet in 2001. “And while René tended to sleep in, another fellow was prone to rising early and firing his rifle. René would lose his temper, go stamping off into the bush and make so much noise that no creature would come within a mile of them.”

These gentlemen were not happy having a Brit (actually, an Irishman who sounds like a Brit who wore an ascot) being brought in to run the show. Dahinden left after a month-and-a-half, but Green and Titmus stayed a little longer until Slick was killed in a plane crash in 1962.

After Slick’s death in 1962, the operations shut down in the Pacific Northwest.

The film Sasquatch Odyssey documents how these four men – Peter Byrne, Rene Dahinden, John Green, and Grover Krantz – worked together and worked separately.

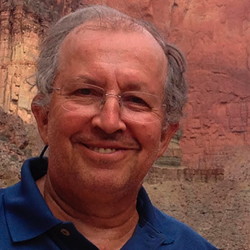

Byrne returned to the Bigfoot hunt in 1971, with funding from Ohio millionaire Tom Page (1928-2020). In 1976, Byrne wrote The Search for Bigfoot: Monster, Myth, or Man? but left the hunt again in 1979. A dozen years later he came back, promoting a no-kill position, when he got new funding from New Hampshire millionaire Robert Rines (1922-2009). Byrne directed the Bigfoot Research Project from 1992 until 1997. In between, Byrne, wearing his trademark ascot, would make a career out of appearing regularly in television documentaries about Bigfoot. In the documentary Sasquatch Odyssey, Peter Byrne told of having used “three million dollars of other people’s money” to search for Yeti and Bigfoot during the course of his life.

In 2017, Todd Neiss reported that one of Byrne’s two wheel covers was given to Neiss.

Byrne could not continue his efforts until the early-1970s, when the Boston Academy of Applied Sciences began funding Byrne (quoted a reporter as $3 million), and Byrne was able to establish a Bigfoot Information Center near The Dalles, Oregon. This effort continued for 9 years, from 1970-1979. During that time, Byrne appeared on In Search Of… and also his own short documentary, titled Manbeast: Myth or Monster in 1978.

Byrne also wrote an early book, The Search For Bigfoot: Monster, Myth or Man in 1975.

Byrne seemingly dropped out of sight after that project was finished until 1992, when he was once again funded by a group to form the Bigfoot Research Project, this time based near Parkdale, Oregon, in the Hood River region. This was a full-scale monster search, complete with helicopters, infra-red sensors and 1-800-BIGFOOT phone number. Byrne’s efforts, which continued until around 1997, did not produce much in the way of good evidence, but he gave it a good shot. After this project, Byrne was commissioned to investigate sightings of a Bigfoot-type creature in Southern Florida, the Skunk Ape. This effort was documented in a production called Shaawanoki, produced by Andreas Wallach and Ronnie Roseman (Byrne got directing credit).

Peter Byrne, 2013

Peter Byrne, 2015, at Beachfoot

Byrne then went into semi-retirement from the Bigfoot field, although he continued his tourist/adventure work around the world. He would often make appearances at Bigfoot gatherings, as, for example, at Beachfoot in Oregon in 2015 and other years (see here).

Peter Byrne, Beachfoot, 2021.

Peter Byrne and Tula Hatti

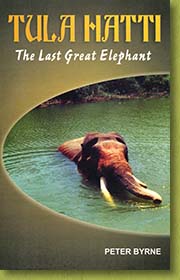

Because Byrne was the primary subject of my Tom Slick book, first published by Faber and Faber in 1989, Peter Byrne approached that publisher about printing his elephant book. Faber and Faber published Tula Hatti: The Last Great Elephant (1991). Byrne continued with part of the Yeti story in this book, when he asked the actor James (“Jimmy”) Stewart to write the elephant book’s introduction about the “removal” of the Pangboche “hand.”

Peter Byrne and the Pangboche Hand

One of the early mysteries of the Slick-Byrne years was the thought that the Pangboche finger bone was lost. When it was found again, we all were told, it was merely that of a “human” relic. No mystery, scientists said.

The result of the DNA analysis was announced on a program entitled Yeti Finger on BBC Radio 4 on December 27, 2011.

In 2011, the BBC stated: “A DNA sample analysed by the zoo’s genetic expert Dr Rob Ogden has finally revealed the finger’s true origins. Following DNA tests it has found to be human bone….Dr Rob Ogden, of the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland, said: ‘We had to stitch it together. We had several fragments that we put into one big sequence and then we matched that against the database and we found human DNA. So it wasn’t too surprising but it was obviously slightly disappointing that you hadn’t discovered something brand new. Human was what we were expecting and human is what we got.’

Thanks to Bryan Sykes book, The Nature of the Beast, we now know that is hardly the end of the story.

In Chapter 19 of his book, Sykes tackles the riddle of “The Pangboche Finger,” and the result he found were startling and shocking.

Ogden’s “human” DNA result was curious to Sykes, and Sykes knew he could find out what mitochondrial DNA it was aligned to. Sykes was able to find that it was “a European mitochondrial DNA sequence, in the clan of Ursula.” The notion that the “human” of the Pangboche finger might be from a monk had to be thrown out. Indeed, Sykes wrote, “The Pangboche Finger sequence was almost certainly not from Nepal or anywhere else close by….” (page 194).

Sykes did the detective work, figured out who was the most likely candidate to have left his DNA on the finger, and compared the DNA to “cheek swab DNA” he had collected. Please read the entire story in The Nature of the Beast. (See my review of the book here.)

It turns out the DNA exactly matched that of Peter Byrne.

<><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><>

Peter Byrne’s Legal Troubles

After years of telephone conversations and communiques, Byrne and I had a break in discussions after my books came out. Then I heard from Byrne on December 12, 2013, out of the blue, saying he wished to “put behind us some of the misunderstandings we reluctantly shared in recent years.” (I won’t go into our detailed history, but Byrne loaned some slides to me and asked me to be his agent with a television program. He ended up being given a fee for their use. The publishing of my book in 1989, on Tom Slick, turned out to have benefited Byrne greatly.)

In light of what was revealed in 2013 across the Internet and Facebook, we all have to make our own judgment about what this Peter Byrne news revealed but it is on the record, and needs to be mentioned clearly, so Byrne’s distractors will not make more it than there is.

These two following items were sourced from official Justice Department “for immediate release” documents.

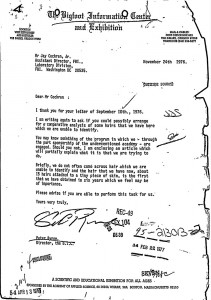

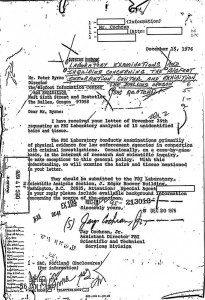

The documents released outline how multiple people had reached out to the FBI after this article but the FBI were, “unable to locate any references to such examinations.

The documents released outline how multiple people had reached out to the FBI after this article but the FBI were, “unable to locate any references to such examinations.

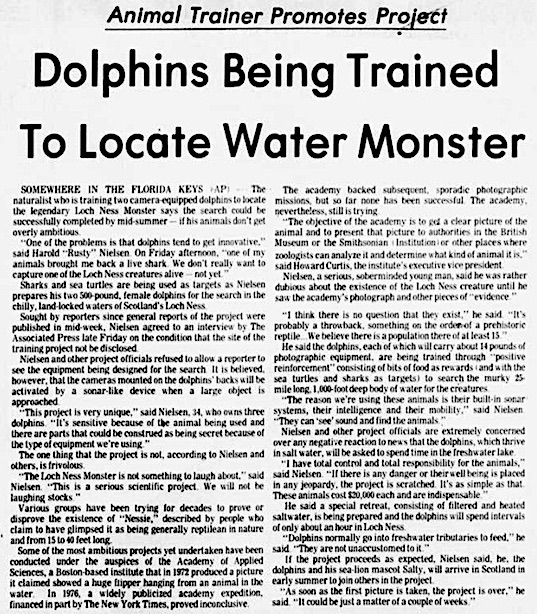

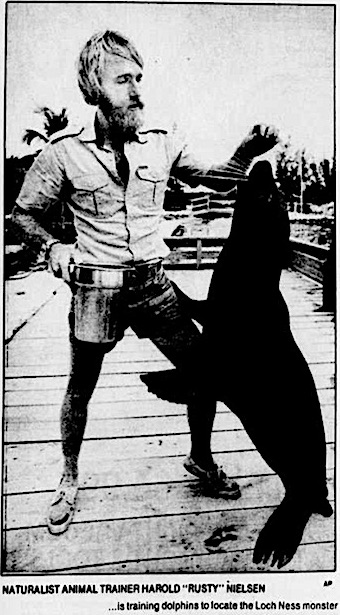

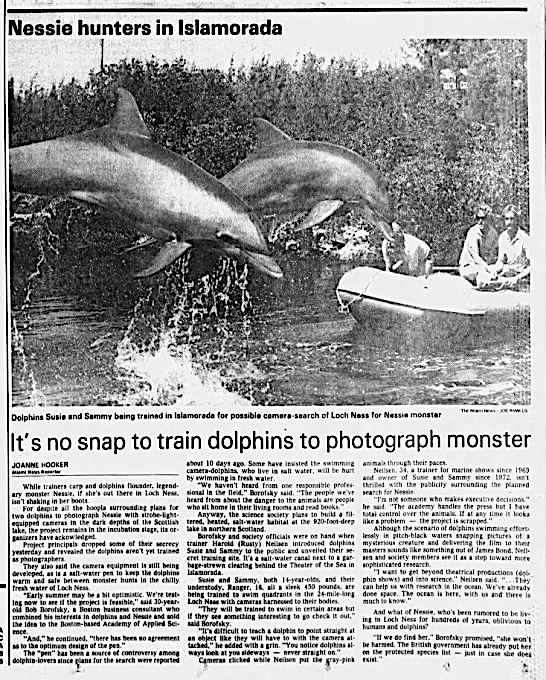

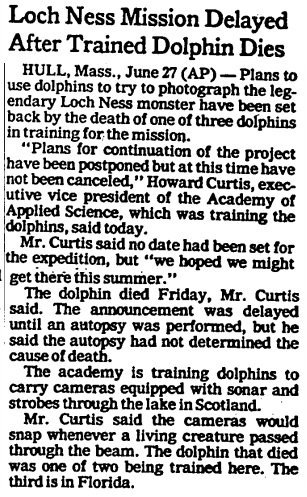

In the letter to Byrne, the assistant director of the FBI’s Scientific and Technical Services Division, Jay Cochran Jr., stated that the hairs and tissue were found to be of the deer family origin. Apparently Peter Byrne was never informed of the Bureau’s analysis because his intermediary, Howard Curtis of the Academy of Applied Science, was too busy training dolphins to find the Loch Ness monster. Robert Rines, who founded the AAS mainly to search for the Loch Ness Monsters, and Curtis had been researching the use of dolphins in the Scottish lake since 1978.

In the letter to Byrne, the assistant director of the FBI’s Scientific and Technical Services Division, Jay Cochran Jr., stated that the hairs and tissue were found to be of the deer family origin. Apparently Peter Byrne was never informed of the Bureau’s analysis because his intermediary, Howard Curtis of the Academy of Applied Science, was too busy training dolphins to find the Loch Ness monster. Robert Rines, who founded the AAS mainly to search for the Loch Ness Monsters, and Curtis had been researching the use of dolphins in the Scottish lake since 1978.

Fort Walton Beach, Florida Daily News, Sunday, March 25, 1979. (Source)

Miami, Florida, The Miami News,

Tuesday Apr 3, 1979, Tue • Page 1

One AAS-associated person quoted as working with the dolphins was named Harold “Rusty” Nielsen (Source).

It is worthy of noting that among the “Deer” (singular and plural) are the hoofed ruminant mammals forming the family Cervidae. The two main groups of deer are the Cervinae, including the muntjac, the elk (wapiti), the fallow deer, and the chital; and the Capreolinae, including the reindeer (caribou), the roe deer, and the moose.

If the samples were found to be “of deer family origin,” of course, they could have been moose.

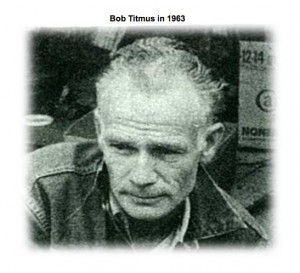

Moose hairs have had an intriguing place in Bigfoot history. The famous taxidermist who taught Jerry Crew in 1958 to make the first plaster casts of “Bigfoot tracks” at Bluff Creek, California, was Bob Titmus.

Naturalist Ivan T. Sanderson found that Bigfoot fecal samples submitted by Titmus actually came from a moose.

The alleged Bigfoot hair samples Titmus found also came from a moose. As has Joshua Blu Buhs noted, Sanderson wondered if Titmus was faking data because California has no moose population, and therefore, there are no moose in or found near Bluff Creek, California, at all. Buhs wrote that this was “deliberate fraud” on Titmus’ part. I raised these same questions originally in my 1989 book, Tom Slick and the Search For The Yeti.

Much speculation has occurred down through the years that Peter Byrne felt pressure from the wealthy men ~ Tom Slick, Tom Page, Robert Rines ~ supporting his Yeti and Bigfoot work ~ to keep producing “material,” “encounters,” and “evidence.” Were any of the hair samples from Bob Titmus’ taxidermy work?

Another Boston-based “business consultant” working for the AAS on the dolphin training was mentioned. He was 30-year-old (in 1979) Robert Borofsky. (It appears Borofsky is now a Ph.D. professor of anthropology, who coined the term “public anthropology,” at Hawai’i Pacific University.)

Robert Borofsky, an academy spokesman, told Sports Illustrated for publication in August 1979, “Everybody knows that dolphins are intelligent, but we haven’t even begun to explore the ways they can be used. They can do a lot more than just jump through hoops.”

The newspapers were filled with stories of AAS training them in March of 1979, but by July, the venture had taken a turn for the worse.

<><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><>

<><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><>

The Aging Peter Byrne

As the FBI Bigfoot news began to break, a focus was placed on Peter Byrne, then 93 years of age. CNBC reporter Dan Mangan tracked Byrne down and interviewed him back then. This article is worthy of reading thoroughly, but let’s look at some excerpts:

When told about the FBI documents showing his correspondence with the agency in the 1970s asking it to test hair samples, Byrne chuckled.

But he also said, “I don’t remember this.”

“It’s out of my memory.”

There is a side of Peter Byrne that few wish to discuss. He frequently says he forgot some things. Mangan dealt with this straightforwardly.

Byrne pleaded guilty in August 2013 to defrauding the Social Security Administration, the Oregon Department of Human Services and Medicaid out of more than $78,000 by concealing his travels outside of the United States from 1992 through 2012.

Byrne, who was sentenced to three years of probation and full restitution, had been receiving Supplemental Social Security Income, and had been required to report to Social Security certain travel outside of the U.S. at times he was getting that need-based benefit.

“Between 1992 and 2012, Byrne traveled outside the U.S. for more than 30 days at least 15 times, on some occasions remaining outside the U.S. for more than four months,” prosecutors said at the time.

He also had more than $85,000 in bank accounts at one time when he was getting SSI and food stamps, authorities said.

According to federal prosecutors in 2013, investigators found a copy of a letter Byrne had sent his publisher, Safari Press, “directing that any future royalties for his published books be sent to his girlfriend.”

“Byrne had previously been questioned by investigators whether he was receiving royalties for the books he had written on topics such as his search for Bigfoot and game-hunting in Nepal,” the U.S. Attorney’s Office for Oregon said in a press release at the time. ”

“Byrne denied receiving royalties.”

<><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><>

Peter Byrne: A Spy?

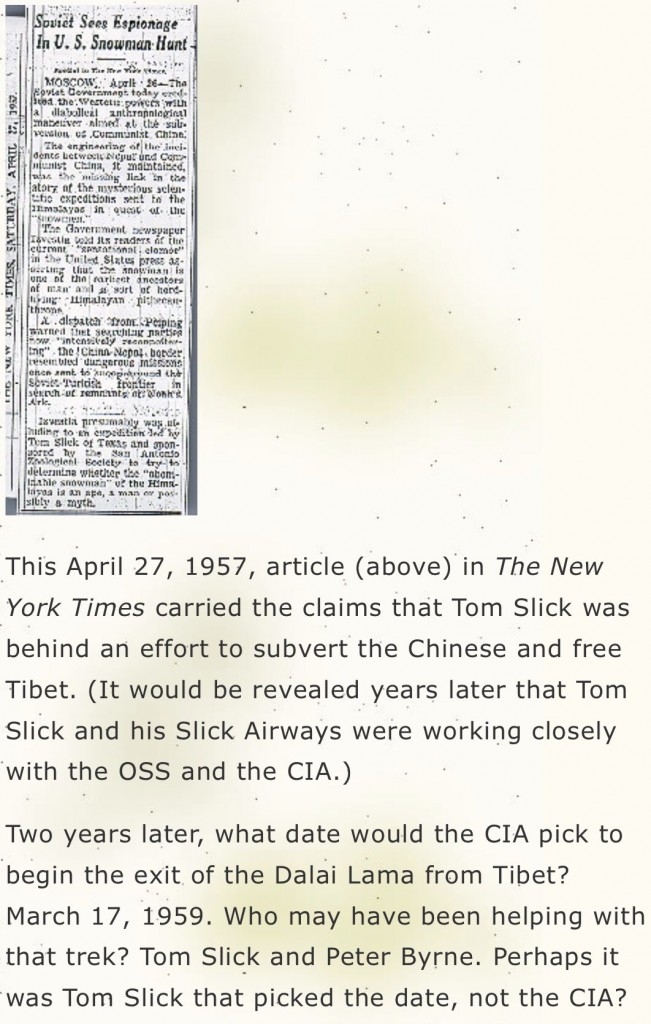

Peter Byrne also appeared to have had a “hiding in plain sight” past that involved the CIA, not in the 1970s, but in the late 1950s. As I noted in my Tom Slick book and elsewhere, the Yeti expeditions of Slick and Byrne allegedly were covers for CIA activity.

Let’s start with one critical incident, the escape of the Dalai Lama from Tibet. There are denials, for example, of the rumors circulating that Tom Slick and Peter Byrne were responsible, in some fashion, for the safe passage of the Dalai Lama from Lhasa. Since the time of Tom Slick’s first official Yeti reconnaissance of eastern Nepal in 1957, in which he was actually a member of the trek, the rumors of his expeditions’ involvement in spying have been rampant. The New York Times even saw fit to publish an article reporting on the Russians’ promotion of this story in an item entitled: “Soviet Sees Espionage in U. S. Snowman Hunt.” The April 27, 1957 piece claimed Slick was behind an effort to subvert the Chinese, and free Tibet.

…Who helped them get into Tibet? None other than Peter Byrne, Tom Slick’s man in Nepal.

~ The Dalai Lama, Slick Denials and the CIA.

More can be found here.

St. Patrick’s Day was always a lucky day for Tom Slick adventures.

<><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><>

The legacy and mysteries of Peter Byrne live on…

Peter Byrne, May 10, 2023. Credit Todd Neiss.

<><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><><>

I knew Peter, talked to him for years, got to spend three+ intense days interviewing him in 1988 for my Tom Slick book, saw him distance himself from me and many others, get in fights with some of the old-timers, and then apologize to me late in his life. I never bore Peter any evil will, and understood that’s what happens in this field. May he rest in piece and find happiness in the hereafter. My deepest condolences to his family, his deep friends, and close associates.

Some books by Peter Byrne

Follow CryptoZooNews

Not Found

The resource could not be found.