Some positive outcomes of the “Finding Bigfoot” clarifications are the solid historical research and timelines that will issue from the tracking of when specific search techniques were developed and used by fieldworkers. Too often in cryptozoological examinations, records and remembrances have vanished, inventors of techniques have died, and a history is completely lost.

With regard to detailing a clear understanding of the histories of wood knocking, a truer history is being developed. For earlier postings on this topic, please see here and here.

It will be recalled that Matt Moneymaker declared to the camera on “Finding Bigfoot” that he was the researcher to have invented the use of “wood knocks” out in the field.

What Moneymaker exactly stated follows:

“Just so you know, one of my claims to fame in the Bigfoot world is that I was the one who discovered that Bigfoots do wood knocks, and that figured out that if you make sounds that they’ll respond. No other Bigfoot researcher had ever figured that out or knew that before, because they didn’t really go into the field that often.” (Transcribed by Melissa Hovey.)

Moneymaker’s claim to this first was also documented on his biography (“provided by Matt Moneymaker, President and Founder of the BFRO” and) posted on the “Finding Bigfoot” site. The passage includes the following:

Matt Moneymaker is well known among bigfoot researchers and is credited with being…

- … the first person who introduced sound blasting and howling as a technique for locating bigfoots.

…

- … the first to formally describe the knock sounds made by bigfoots in 1992, at a scientific conference at Rutgers University for the International Society of Cryptozoology.

This has served as a research challenge to archival investigators and historians of hominology. The research questions are, therefore, when were the first accounts of wood knocking and who first used the earliest discovery and awareness of wood knocking to entice Sasquatch to respond?

As with the research being done on the history of call blasting, we need to extend the historical investigation of the first casts, the first hair sampling, and the first notice of dermal ridges. Of course, many of us think we know who did what first and when it was done, but as has been said already and has been revealed this week, we all have different pieces of the puzzle that need to be shared so currently still-writing historians like myself, Dmitri Bayanov, Michel Raynal, Jean-Jacques Barloy, Jeff Meldrum and others can chronicle the reality behind the assumptions.

So, let’s look at look at one phase of wood knocking again, an early account of its awareness in the literature.

The Tlingit (also spelled Tlinkit) are an indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Their name for themselves is Lingít, meaning “human beings.”

The Tlingit are a matrilineal society that developed a complex hunter-gatherer culture in the temperate rainforest of the southeast Alaska coast and the Alexander Archipelago. An inland subgroup, known as the Inland Tlingit, inhabits the far northwestern part of the province of British Columbia and the southern Yukon Territory in Canada.

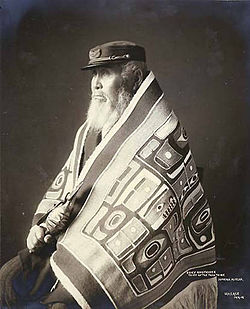

Chief Anotklosh of the Taku Tribe, wearing a Chilkat blanket, Juneau, Alaska, ca. 1913.

Among the Tlingit, there exists creatures with the name Kushtaka that appear to be somewhat similar to Sasquatch. Their name is loosely translated as “Land Otter Man.”

A Kushtaka mask from the Stonington Gallery.

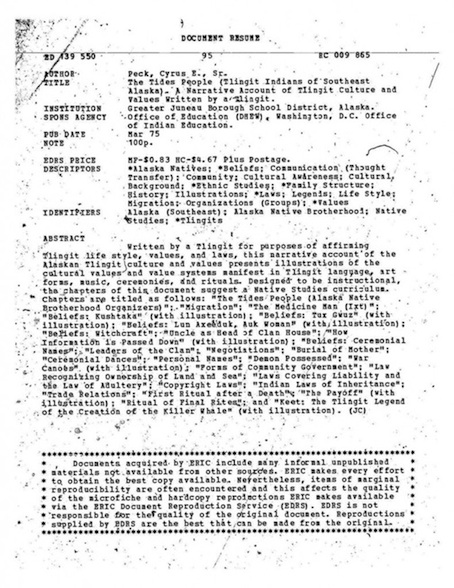

In a 1975 paper by Cyrus Peck on the Tlingit, these First Peoples describe tree or wood knocking produced by these hominoids:

“Kushtaka is a weird looking creature who might be glimpsed darting from tree to tree keeping out of range of the observer. it moves like the wind and disappears at will only to reappear again elsewhere, all the time keeping its hand before its face and peering out at times through its fingers. The shock of seeing it is tremendous. Whenever Kushtaka catches and breathes on its captive, he looses all sense of reality until the Kushtaka leaves.

“Hearing Kushtaka in the forest is a sound similar to that of someone hitting a tree trunk with a club.”

“‘Ahs da do hished,” the Tlingits would say. “Someone is hitting the trunk of a tree.’”

Here is a copy of this passage from this paper:

And the cover sheet with the citation of the paper:

Follow CryptoZooNews

Not Found

The resource could not be found.