Grover Krantz’s quickly stated theories, sometimes, need to be called into question.

Take, for example, his notion of what was behind the sightings of “Stone Giants” or “Stone Clads” in Eastern North America.

Krantz’s bias against Eastern Bigfoot reports, in general, boils to the top in his discussion of these hominoids.

On page 143 of Bigfoot Sasquatch Evidence, Krantz writes: “Native stories that can confidently be related to the Sasquatch occur throughout the Pacific Northwest. Their distribution closely corresponds with the area where White Man accounts are concentrated. Attempts have been made to relate native stories from other places to the same phenomenon, but with little success….In the eastern part of North America there are stories of the ‘stone clads’ who strike with lightening from their fingers. To me this sounds more like an exaggerated version of early encounters with armed and armored Vikings, if it has any physical referent at all.”

I frankly think Krantz is too shortsighted about this. From doing historical research on Native traditions and looking at the evolution of the motif of “stone clad” Wildmen, I came up with a different hypothesis than Krantz’s “Viking” explanation.

Within the eastern Native Americans’ folklore and stories there exists the background for understanding how Marked Hominids/Eastern Bigfoot/Windigo got from being hairy to stone covered and finally to a state where they would be called “Stone Giants.”

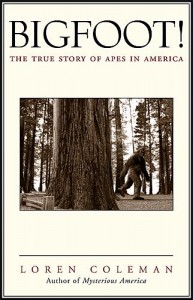

In Bigfoot!: The True Story of Apes in America, (NY: Simon and Schuster, 2003) by Loren Coleman, I wrote:

In eastern North America, a specific subvariety of manlike hairy hominoid allegedly exists. It exhibits aggressive behavior, hair covering the face in a mask like fashion, occasional piebald coloring, an infrequent protruding stomach, and distinctive curved, five-toed sprayed footprints….They are inhabitants of the northern forests of the East. The local Native American, Native Canadian, and Inuit accounts discuss the ancient traditions of these hairy humanlike beings with words special for each linguistic and tribal group. Nevertheless, a casual practice has begun to develop in the East in calling these hominids “Windigo” in association with a commonly used Native regional name from long ago. The Algonquian linguistic groups of the East and upper Midwest of the United States and Lower Canada have used the terms Windigo, Wendigo, Weetigo, Wetiko, Wittiko, and other variant names for these reported giants of the bush covered in hair.

* * *

There was a free exchange of information on these manlike hairy primates among many First Nations in eastern North America. In the eastern provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia down into Maine, the Micmac tell of the Gugwes. “These cannibals have big hands, and faces like bears,” noted folklorist Elsie Clews Parsons in her 1925 paper in the Journal of American Folklore….

The cannibalism attributed to the Windigo is specific to these eastern hairy hominids. Anthropologist Grover Krantz, who seems to not have studied these traditions closely, is to be excused for falling into the usual misunderstandings of these traditions of the Windigo when he too quickly senses they all have been based on stories of cannibal Indians. The Natives clearly thought of these hairy cannibal giants as non-Indians.

The Micmac know the cannibal giant by the names of Gugwes or Koakwes and Djenu or Chenoo. However, Wilson D. WalIis and Ruth Sawtell Wallis in The Micmac Indians of Eastern Canada note that “Gugwes is a grotesque creature; in 1911-1912 he was commonly compared to a baboon; in 1950 he was described as a giant.”

In the state of Maine, the Penobscot tell of the Kiwakwe, a cannibal giant (Speck 1935b: 81). “The giants, or Strendu, the averred enemies of the Wyandot,” relates C.M. Barbeau in recording beliefs of the Huron and Wyandot in the area of Lake Huron, “were dreaded on account of their extraordinary size and powers. Some describe them as being half-a-tree tall and large in proportion. Their bodies were covered all over with flinty scales, which made them almost invulnerable.” The Strendu, too, are said to be cannibals.

In Upper New York State similar beings were known as Stone Giants. “The Iroquoian Stone Giants,” notes Hartley Burr Alexander in Mythology of All Races, “ as well as their congeners [a member of the same kind, class, or group] among the Algonquians (e.g. the Chenoo of the Abnaki and Micmac), belong to a widespread group of mythic beings of which the Eskimo Tornit are examples. They are. . .huge in stature, unacquainted with the bow, and employing stones for weapons. In awesome combats they fight one another, uprooting the tallest trees for weapons and rending the earth in fury . . .. Commonly they are depicted as cannibals; and it may well be that this far-remembered mythic people is a reminiscence, coloured by time, of backward tribes, unacquainted with the bow, and long since destroyed by the Indians of historic times. Of course, if there be such an historical element in these myths, it is coloured and overlaid by wholly mythic conceptions of stone- armoured Titans and demiurges.”

More of these peculiar “primitive” tribes are identified, as noted, by these First Nations as the Windigo of Algonquian origin. Knowledge of the Windigo is extensive and well documented in eastern and central Canada. The Tete-de-Boule of Quebec use different names for the same being: Witiko, Kokotshc, Atshen. The Chenoo of the Micmac seems to be similar to the Witiko of the Cree, for John Cooper in his article on the Witiko in Primitive Man observes: “Both have the same characteristics . . .. The very name Chenoo seems to be identical with the Montagnais and Tete-de-Boule (Cree) name, Atcen, for the Witiko.” According to anthropologist Frank Speck, among the Naskapi “the nearest analogy in name and character with Atcen among neighboring peoples is the Chenoo (Tcenu) of Micmac legend.”

The traits of the witiko, recorded by Rev. Joseph Guinard, in his article “Witiko Among the Tete-de-Boule,” in Primitive Man, recall traditions elsewhere: “The witiko wore no clothes. Summer and winter he went naked and never suffered cold. His skin was black like that of a negro. He used to rub himself, like the animals, against fir, spruce, and other resinous trees. When he was thus covered with gum or resin, he would go and roll in the sand, so that one would have thought that, after many operations of this kind, he was made of stone.”

A similar habit, observes John Cooper in “The Cree Witiko Psychosis,” in Primitive Man, “is ascribed to the Passamaquoddy Chenoo who used to rub themselves all over with fir balsam and then roll themselves on the ground so that everything adhered to the body. This habit is highly suggestive of the Iroquoian Stone Coats, the blood-thirsty cannibal giants, who used to cover their bodies carefully with pitch and then roll and wallow in sand and down sand banks.” ~ from Bigfoot!: The True Story of Apes in America.

Follow CryptoZooNews

Not Found

The resource could not be found.